Report made with the support of Oxfam Intermón

Sinta, the taxi driver who shows me Addis Ababa from end to end, gestures dismissively when I ask him about the past. «Now we’re fine!», says with conviction. We meet very early in the morning in order to climb the Entoto Park, from which you can see the whole city. It has to be early because the engine of his Soviet Lada, he explains, is made for cold temperatures, and at certain hours there are slopes that it cannot bear.

He doesn´t understand what interest the communist years can have, which were particularly bloody in Ethiopia, or the consequences of the war with Eritrea. «That was ridiculous, a stupidity!» he states. In the eighties he lost a brother in the front. But all that is already forgotten, he insists. It´s over.

Hunger has always been connected to political change in the recent history of Ethiopia. It was the documentary about hunger, “The Unknown Famine” (Jonathan Dimbleby, 1973) that marked the beginning of the end of the reign of the emperor Haile Selassie. During the communist regime of his successor, Mengistu Haile Mariam, the political use of hunger plunged the nation into of the most catastrophic and darkest periods that humanity has ever seen. According to Robert Kaplan in “Surrender or Starve”, the fight against hunger served as an excuse for the communist dictator to carry out massive deportations and the fees he charged for humanitarian aid entrance into the country served to finance the war against Eritrea.

News of these famines spread widely through media coverage. Images of starving children marked a generation in the eighties. The impact was so strong that in 1989 the General Assembly of European NGOs adopted a code of conduct to avoid future campaigns focusing on the sensationalist aspects of life in the developing world and oversimplifying the image.

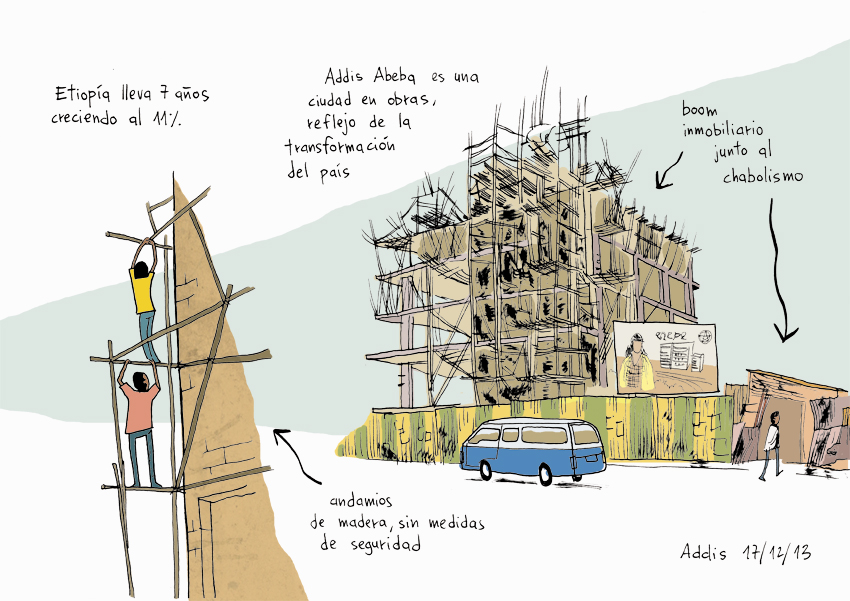

In fact, this image has long been in the past. Ethiopia has been growing for the last seven years at a rate of 11%. In the context of the international crisis, the economy has dropped to 7.5%, but Eduardo García Reneses, accountable for cooperation programs in Ethiopia, believes it is still “robust”. In December, an article in the Addis Ababa newspaper, The Reporter, stated that by 2025 Ethiopia hopes to become part of the “middle level” group of countries with development plans that are already under way.

The memory of famine remains present in the minds of various generations in Ethiopia. In this country macroeconomic data is not enough for the future, and it is something the government knows well, maintaining the fight against hunger and poverty as a main objective or, at least, the most publicized. However, there is still a major deficit in governmental investment toward the construction of the infrastructures which provide access to essential basics, like water, in safe conditions. There is willpower and there are plans, but financing is usually missing. Access to water is one of the biggest hindrances keeping many regions of the country underdeveloped.

According to this year’s results from the NGO ‘Water AID’, in Ethiopia 43.4 million people, over half of the population, do not have access to clean water or safe water sources. The rural population frequently suffers from parasitic illnesses like amoebiasis, acariasis, schistosomiasis, and diarrhea from illnesses like giardiasis. According to the 2006 Intermon Oxfam figures, 169 children of every 1000 die before the age of five. In some parts of the country, 40% of deaths are caused by water related diseases. Added to the lack of infrastructure is that the population doesn’t know what types of sicknesses are provoked by drinking unclean water.

Through Oxfam Intermón, Jot Down visited an humanitarian project that consists in something as simple as establishing safe water points. A simple mission, but that it´s transforming society at all levels.

The Oromia region is the biggest in Ethiopia and is also the most populated being home to 28 million people. Twenty four percent of the population here doesn’t have access to safe water. The landscape is green. There is nothing particularly exotic. It is very close to the prairies and mountains of the Iberian Peninsula. Asefa Gelmessa is a doctor in Ginchi Town, in the woreda – region, in Amharic – of Dendi. Although the shortage rate is almost half of that in the rest of the country, the doctor says that diarrhea is the most common malady.

When the locals notice the symptoms, if they don’t immediately go to the hospital they can die of dehydration. If they are treated, recuperation tends to take about seven days. For many farmers this is a problem because they can’t work during that time. But, the most affected by this problem are children under five years old.

The Medical Center in Ginchi Town, continues Gelmessa, doesn’t have enough medicine, but as he explained, even more important than medical equipment – with what is available they are able to treat the patients they receive – is the arrival of clean drinking water and the building of latrines. The government tries, he says, but doesn’t have sufficient funds.

Nevertheless, in Dendi Woreda, Intermon Oxfam and its local partner Water Action have completed the construction of 60 kilometers of pipes to bring water to an entire valley. The construction brought about a small revolution and is becoming the basis for profound changes in the local life conditions.

The pipes bring water to 10 kebeles −towns, in Amharic−, some 40,000 people. Regional authorities boast that 56% of the population already has accessible sources of drinking water. They are confident to reach 100% in the next years with the help of the cooperation. For the moment, those 60 kilometers of pipes have improved the health of the locals and have served to educate thousands of children, especially girls.

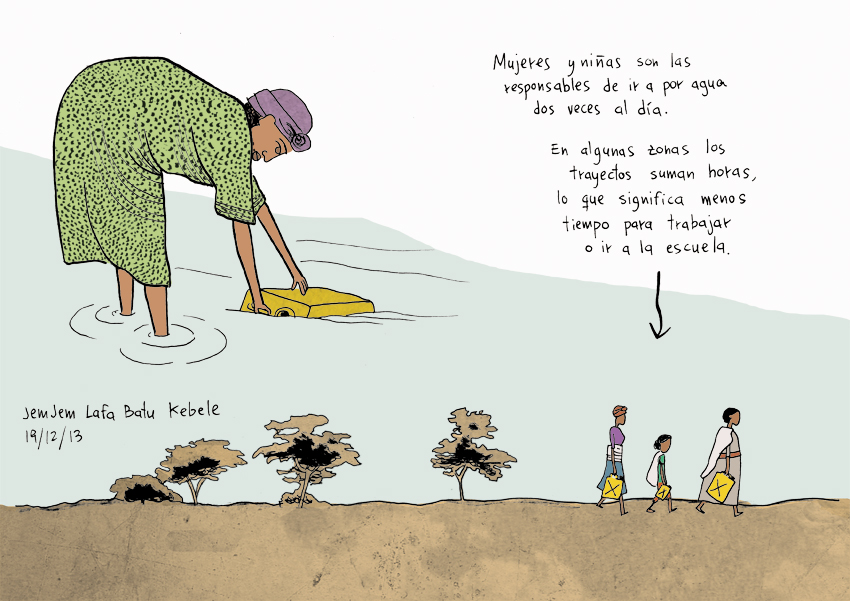

Traditionally, women were in charge of getting water in their communities. The routine was to make the trip a few times a day, on routes which could be three or four kilometers long. It was enough for girls not to be able to think about school or studying. In addition, the long walks exposed them to mosquito bites carrying malaria, making them even more likely to get sick. A safe water source in their kebele has given many girls the chance to go to school. The construction of separated latrines in schools has also made is possible for girls to go to school when they have their period, informs a representative of the Health Department of Dendi Woreda. Before, menstruation was a reason for prolonged school absence.

As for the Economy, in Ethiopia “there are more cows than people”, explains Reneses. Now that the animals don’t have to be taken long distances to drink clean water, they can gain weight. A few extra kilos on the cow inject liquidity into the family economy.

On the torturous walk to the first water post at the springs of Worka Gara Kebele, the importance of children to the local economy is confirmed with every step. Small children, no more than six or seven years old, can be seen pushing a plow with oxen. And you can not talk about child labor and explotation as in other places, it is a system of traditional work in the field that distribute the liabilities among the whole family. Rows of children and adolescents are cutting wheat with sickles. Even though the country invests in modern machinery to mechanize agriculture, combine harvesters haven’t arrived here yet. We talked to two brothers, who are shepherds, resting under a tree. They explained that only the youngest can go to school.

The managers of the first water tank are Kifie Desfa and Amerewerk Chekol, husband and wife farmers. They are of Oromo ethnicity and are rural people with strong spiritual beliefs. The wife confesses that the economy hasn’t changed substantially since the arrival of drinking water because it is not “one person who needs many things”, but she explains clearly that now people don’t get sick from drinking water. Before, the river passed in front of her house; she was periodically ill, but didn’t know why.

The first town to benefit from the new plumbing is on the hillsides of the mountain. The air is fresh and pleasant, but the sun burns. The young people are around two foosballs and play eager. Some seniors are drinling tala, homemade beer, in a small bar that is at the other side of the kebele. Kebede Keru tells how he built the latrines and the showers so that people wouldn’t take care of their business outdoors. According to the mission of Intermon Oxfam, it is difficult to convince the rural people that they have to use the toilets. The latrines often get dirty and the people think it is healthier to do their business somewhere else, which means that they are constantly surrounded by concentrations of infection. The mission of the NGO does not end with getting water to the town. Educating people to acquire health habits is very important too.

All of Kebede’s children go to school. They have placed the pump in the center of the kebele, his wife, Zargi Negasa, is the cashier. She’s in charge of charging everyone who uses the water and taking the money to the bank. She can only do it for one hour a day, usually in the morning. At night, the citizens save their spot by putting their containers in a line in front of the pump. The well is fenced off and closed with a key so that no one will misuse it and so that the cattle won’t contaminate the area with their excrements. Zergi Negasa was a volunteer in the committee that started the project. She had to go door to door convincing her neighbors to voluntarily work on the canalization to the kebele.

The pipes have 60 distribution points like this. With the money raised from its use, 40% is paid to the professional operators who take care of problems and 60% is used to maintain the infrastructure. Everyone on the board of directors is a volunteer.

Since getting safe water has made children less necessary in everyday tasks and allowed them to go to school, the next urgent necessity the communities face is building schools. One example is Nubarite, built by the initiative of the locals, who constructed it themselves when the government gave them the authorization.

In the middle of December there are no more than half a dozen students in the school. It is harvest season and classes are suspended so that the children can help their parents with the field work. Nevertheless, the director, Arasa Tasisa, says that normally there are between 80-90 students per room. The arrival of water and the installation of latrines multiplied the number of students. On days when there are no students, workers, recruited from the town, carry out maintenance work in the building.

Johannes is the director of the valley canalization project. He explains that when they finished the source to bring water to this school, the first time the faucet was turned on not a single drop of water came out. They had to dig up kilometers of pipes until they found the obstruction. The repair took two years. This is only one of the hundreds of difficulties that the project has faced. He says it has been “like getting with a university degree”.

But water still hasn’t arrived to all of the key points in the region. At the school in the Aanaa Dandii district (where we found signs in Oromo) the children take turns drink water hanging from the handle of a pump at recess. There are 428 students between 4 and 14 years old and seven teachers. One of them explains that the kids are often sick with digestive illnesses related to the water and even with malaria, which is complicated to contract at their altitude. When a student is sick he usually misses up to two weeks of school.

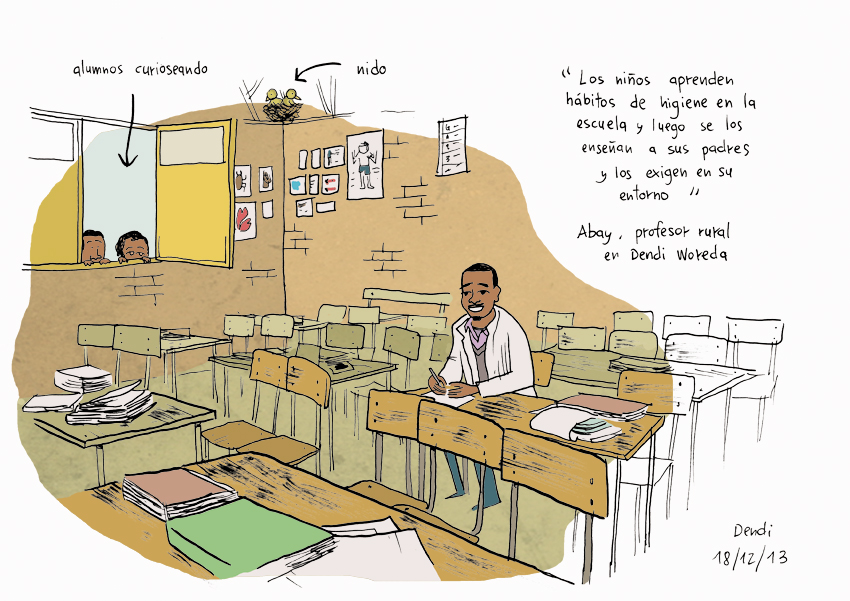

The teacher confirms that since the kebeles started receiving safe water sources, it is more common to see girls in class. Although, he complains that they still cannot dedicate much time correctly finish their homework because they must help with household duties. Teaching hygiene is more important than any other subject, he continues, obliging students to be clean and keep the school clean. The children learn healthy habits and later they teach them to their parents and expect the same in their surroundings. The students learn to boil water and wash their hands before meals– Ethiopians, whatever their social position, don’t use silverware to eat.

This school was built by Save the Children in 1999 (our 2006) of the Ethiopian calendar Ge’ez, the Julian calendar for Orthodox Christians. It started off as a nursery school, but in the last seven years has started giving classes to children from 1st to 6th grade, as a result the space is getting small. The head of the center remembers when they started the school the majority of the children where dirty. Little by little it started changing, he says. Now more and more children wear shoes and parts of the uniform, a green suit, which is difficult to see complete on any student. They wear what they can find; what their parents can afford, he explains.

The biggest difficulty which these children face in their education is that their parents can’t help them because they haven’t got an education, the teacher reveals. Although many maintain a farmer mentality, they are eager to learn, he says, but in many cases they don’t have access to means of communication and that is a disadvantage for progressing in their studies. The media isolation of the children was confirmed on the spot. A cameraman for “We are Water” had gel in his hair. When the students saw him they formed groups in the patio. They approached him and timidly asked in English, “Are you Cristiano Ronaldo?” They had strong suspicions that he could be the Portuguese footballer.

In the rural countryside, for years children have been born simply as an economic resource for their parents. They served to help with the cattle or in agricultural work. There is no kind of family planning. The older generations don’t know the value of education, a teacher confesses, although now something has changed in their mentality and the farmers want their children to go to school.

Some of the students who have passed through this school in the past seven years have been able to go to high school and later university, but very few, he notes. The tests are a difficult challenge for them. Only two or three out of fifty make it. If they pass, hard sacrifices await them. They have to go to the city and survive there all week, in some cases, on only a few pieces of bread.

But, being educated in the middle of the countryside can also have advantages. In class, for example, they have a bird’s nest. The babies have recently hatched from their eggs and are a part of our conversation. Using everything available to teach the teacher considers that he is strengthening the creativity of his students. It is the only added value he can offer them.

Apart from water, education faces other difficulties as well. In the kebele Yubdo, Dejene Hirico is happy to have clean water near home, but also wants the government to provide electricity. Of all of the difficulties due to this, one stands out: “My children can’t study without the right light”.

In any case, it appears that life is improving. When he was a student, during the years of the communist dictatorship of DERG, only the privileged kids could wear uniforms, her remembers. Now it’s possible for everyone, he says. In addition he had to hide in the forests to not be enlisted in the army for the war. In this zone the forced recruitments were a generational tragedy. Johannes remembers that boys were prepared for war in school and that families celebrated having a daughter as a blessing. The wash officer of Intermon, Abayneh, lost a brother. He is one of the thousands who disappeared during the eternal conflict with Eritrea. A recent film, “Teza” (morning dew, in Amahric), by independent director Haile Gerima tells story of the suffering families endured in the 1980’s. What you see in the film is the same thing that the locals tell you.

In Yudda, a woman, Galane Geremo, shows us the interior of her house and proudly shows is the latrine that was built on the surrounding land. Her children are in charge of keeping away their goats and sheep so that they don’t cause problems. Galane shows us her bathroom, holding her mobile phone in her hand. Telecommunication has arrived before water in this community.

In fact, AVKO Fundation has developed a mobile phone application to locate water reservoirs and mark creeks. In Ethiopia, UNICEF is implementing it with the local authority. With this initiative they hope to improve the living conditions in the low lands (Oromia in in the high lands, which are greener and wilder). The nomad groups live in this zone, pastoral people who live moving their herds from one place to another. The incidence for water related illnesses in this population is very high.

Abayneh explains that for as long as he can remember water has always been a problem in his country. Even in Dendi Woreda, Jamjam Lafa Batu Kebele still hasn’t got water. The ambiance is noticeably different in communities where sanitary construction has already begun. One woman, Akeclamariem Assefa, says that her children only drink water at school, if they drink water in the kebele they get sick. She tries to boil the water, but she can’t heat the 40-50 liters that her family consumes every day.

The economy of the kebeles is protected by a cooperative regime. The system was imported from India and allows local people to buy basic products at reduced prices at community shops in exchange for their crops. The positive results cannot be denied, says a member of a local NGO, although intermediaries purchase crops at too low prices. At AECID (Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation) they explain that it is very complicated for the common farmer to take his products to the points of sale due to the structural problems of the roads and the channels of communication.

Although the use of fertilizers and compost has increased their production and quality, they don’t have access to the markets. They also don’t have warehouses to accumulate and save the excess.

The IMF says that to sustain the rate of growth and make all the necessary structural reforms, Ethiopia should increase the private sector. Currently, the country still maintains in public control the “crown jewels”, as they are called: energy management, telecommunication, sugar crops, and Ethiopian Airlines. Even the financial system is 100% public, the private bank doesn’t exist. The government controls all the savings to finance their investments, but none of this is included “in the national budget, if it were, the deficit would shoot to 10%, a worrying figure”, explains Reneses.

In this situation, it continues to be difficult for the children of the kebeles to reach the university and become part of the slowly growing middle class. The phenomenon exists, but thanks to great sacrifices. Abayneh remembers a university classmate who was born in one of these kebeles. “He went to class at night, during the day he worked cleaning shoes in Addis Ababa to survive. He ate the food we left on our plates when we’d finished eating. Today he is a doctor”.

A graduate of Economics who was also born in a kebele, Dinsa Girmaye, remembers that he also had classmates who lived in these types of situations, not only at university, but even in high school.

At that time there were no refrigerators in the towns or in the cities. Lots of my friends, who studied in the city and were from towns, had to go three or four days walking to return home to get food, their parents couldn’t afford to let them buy food in the city. Very few were able to study in these circumstances.

After finishing their university studies, many graduates leave the country, except for those who study under government scholarships and have the obligation to stay and work for the government for a few years. There are divided opinions about the graduate exodus. Some think that young people today are only interested in money, as school teacher Aanaa Dandii complains. The spirit of those who want to return to their community what they have been given prevails. But, there are also those who understand the situation. Ethiopia is not lacking for problems, among them, one from the European Parliament for the lack of human rights. A doctor, who works in public health because he studied under a government scholarship, says it is normal that many people want a better life outside of their nation. In any case, the remittances from emigrants are one the most important sources of income in the country.

The doctor speaks bitterly about the streets of Addis Ababa. They are among the safest in Africa, but, “at night you can see many children who suffer physical and sexual abuses and it is a very serious problem for which the government doesn’t have a solution”. The subject appears in the press. The Daily Monitor headlines one of its December editions saying that Ethiopia is a top-ten country for “unknown children”. Seven percent of the children don’t officially exist. “The statistics say what the statistics say”, a foreign worker ironically states remembering the 100% rates of school attendance that the government boasts.

On the other hand, another social divide is opening due to rising prices. In the last years prices have multiplied. Retirees can no longer pay for their basic groceries and children are taking care of their parents. In the capital, the presence of civil servants of embassies and the African Union, whose headquarters are here, along with 100% taxes on imported products, life is more expensive than many European cities.

In the entire country there is a frenzied passion for English football. A group of middle class youth says that because prices are so high for everything, they prefer to spend the little they have on a beer while watching the matches. Meanwhile, laborers and manual workers in the capital have long days and low salaries, about 50 birrs (2 Euros) a day. They drink Tala, a homemade beer, and chew khat, a stimulating plant. Their meeting places are marked with a can on a stick at the door of each building, it indicated that in this house is sold homemade beer.

On December 16th, in the newspaper ‘Fortune’, columnist Girma Feyissa complains that young Ethiopians aren’t interested in the history of their country and saying, “I can’t think of anything as powerful as football to keep everyone united (…) No propaganda or rhetoric enjoys the same amount of attention as football”. But, this is above all in the cities.

Returning to the kebeles, the construction of plumbing has forced rural communities to work together. One technician of Water Action explained that the attitude of the locals is to help the rest of the communities with their work so that sanitation will reach their own town as soon as possible. Helping others to help yourself, a more uplifting philosophy than soccer.

Illustrations: Ferran Esteve

Photography: Álvaro Corazón Rural (full gallery here)

Translation: Dianne Conn

Pingback: Etiopía, agua que riega la salud y también la educación