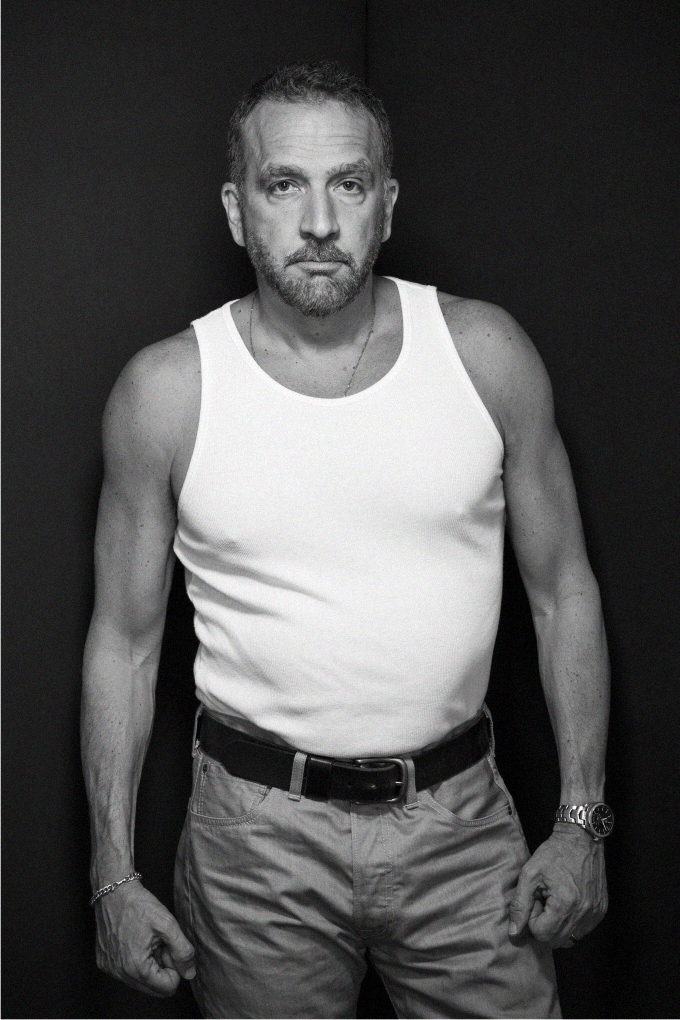

George Pelecanos is a Greek American author born in 1957. He has written dozens of detective novels, all of them full of redemption, masculinity in the best sense of the term, and codes of honor. They also include basketball and funk, cool cars and lots of morality. Pelecanos is, as almost everybody knows, a TV and cinema writer and producer. His most famous works are the HBO shows The Wire and Treme. George Pelecanos still lives in the same neighborhood where he was born, in Washington DC, with his wife and three kids. When we talk with him we confirm that when an artist becomes famous in the whole world doesn’t have to lose his enthusiasm and cordiality. Pelecanos is constantly laughing, and every time he looks back he seems to be living again those moments of bliss, flair and big expectations which shaped his spirit and work.

I’d like to start talking about your background: your teenage years, your jobs, working at the diner…

Well, it’s a lot… My dad was born in Greece and my mum is also Greek, but born in America, so I’m 100% Greek. My father had a diner in Washington DC, and I started working there when I was 11 years old.

And later your father got sick.

When I was 19 my father had a heart attack and cancer in the same year and I dropped out of college to run the business because otherwise my parents would have lost it. And the reason I could do that is because I’d worked there from the time I was eleven, so I knew what to do. The thing that was so influential for me on many levels was, first of all, seeing my father work so hard and figuring out as a kid that that’s what a man does. He gave me my work ethic. Also, the social milieu of Washington at the time. When I started going down there on the bus was right after the ’68 riots. It was just so much being thrown at me in terms of looking at the people on the bus and watch the city being burn… And then go on to the diner, where it was my dad and me, Greek-Americans, and then all black employees behind the counter, about five of them, and on the other side of the counter it was all white people wearing ties. And in the background was the music playing out of a soul station because my dad let the employees to play whatever music they wanted during the day on the radio. We had two station on AM that played soul music and because it was south of the Mason-Dixon line, because DC is the beginning of the South, the soul music that was being played was generally not Motown or northern soul, it was southern soul. It was Otis Redding…

Deep soul.

Yeah, deep soul. All this stuff was kind of happening to me at once. As a kid I didn’t really understand it on an intellectual level, but on a sensory level it was all coming at me.

You knew where you stood, from the beginning you knew that you were on that side of the counter.

That’s right. It’s why I write about the things I write about. They all go back to that. It’s why my books are pretty much about working-class people. Southern Washington, the federal city, the politicians, people with money… I’m not from that world, but I am also not interested in that world. I’ve done very well in life, so I can’t deny that now I’m sort of one of them now, but it’s not the way I live my life, I still live in the neighborhood I grew up in.

Nelson Algren used to say: “I might be in the middle class but I’m not middle class”. I wonder if that’s the way you would describe yourself.

True. Actually, I’m in the 1% of the country, I’m in the top earners, but I don’t feel like it. That’s not who I hang out with, that’s not where I live… Having money is fine because it’s one less thing to worry about, I don’t wake up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat wondering how my kids are going to make it. But that’s all it means to me, really, because I’m still doing what I’ve always done.

Working people sometimes are derided for doing better for ourselves. Are we expected to be working in supermarkets all our life? That’s an obscene way of looking at the world.

I think it’s ridiculous. Again, watching my father it was all about trying to better himself. Compared to me he was from a really poor background, the kind of background where you only had one pair of shoes and there were no toys at Christmas. That sort of thing. He certainly gave me a better life and my goal was to give my children a better life and to progress. It’s not a bad thing unless you forget where you came from and you don’t look back. I always say I’m a capitalist.

Your lifestyle has changes dramatically since you were a kid, but do you think, quoting D’Angelo from The wire, that what came first is who you really are? Are you still that Greek kid?

I really feel like I am, but I am calling you from my beach house, if you see me doing a public appearance, like reading, I’m wearing a beautiful Italian suit and I drive a Mustang that I love. But I’ve done things, that’s the reward of working hard. But I also give a bunch of my money away every year to organizations that help kids in the city, I do reading programs in prisons… It’s possible to do both.

At the beginning of this interview you said you are 100% Greek. Are you what a Greek is supposed to be like?

There are certain things that are true. One of the things is that we do work very hard. You don’t see a lot of Greeks in this country who are on welfare, they figured it out. And it’s not because we are better, it’s because you do what your parents do. You look at Greece and what’s going on there now with the rise of these fascists is shameful. One of the things that I’ve been trying to talk about is that Greeks all over the world need to stand up and condemn that because that’s not who we are. And it’s all about the economy, obviously. It’s what happened in Germany in the 20’s and the 30’s. That gives rise to fascism, but that’s not us.

One thing I love from your novels is that they are very masculine, in the better sense of the word. I read that the films you watched when you grew up gave you this sense of a masculine world, with coats of friendship, honor, loyalty. I think it’s great that someone like you decides to talk so much about masculinity, because it’s a fascinating world.

I agree. I don’t see a lot in books where it’s honestly dealt with what it means to be a man, with all the faults as well, and trying to stay straight in the face of temptation. And also the need to prove yourself physically. There was a time when that was sort of out of fashion, any physicality, like when a man got in a fight, was seen as dumb. But there’s something that goes back to your boyhood when you’re challenged. I am more ashamed of the few times that I walked away from a fight than I am from losing fights. I should have stayed and I should have got my ass kicked instead of walking away. It’s embarrassing. Sometimes violence is necessary, it’s cathartic.

And sometimes violence is the only reasonable response to injustice. Woody Allen said in a movie that you don’t go to Nazis with books, you go with baseball bats.

[Laughs] Yeah.

One of the things that interest me about manliness, which also comes through in your novels, is the need to protect yourself, to hide your weaknesses. Sometimes your characters try to hide their feeble points with a display of strength.

Bravado.

Yes, exactly.

Yes, they put up a front.

And it’s something all men do.

Of course, people have insecurity and they try to deal in different ways, men especially. You sort of hinted at it, I got a lot of this stuff from watching movies when I was a kid. I am one of the few writers that will admit that I was probably more influenced by movies than I was by books. I am more about Gregory Peck and Tyrone Power than I am about William Faulkner. Sergio Leone, Robert Aldrich and Don Siegal influenced me much more than Faulkner, Hemingway or Fitzgerald. Those movies shaped my worldview in a lot of ways. I came to books pretty late, I was a senior in college when a teacher turned me into books and told me I should read this. I got turned onto books because of one teacher. I had wanted to be a filmmaker. How does a Greek kid from Washington DC become a filmmaker? I had no idea, I hadn’t even left Washington, I hadn’t travelled at all.

That step from where you stood to filmmaking felt like sci-fi.

Yes, how could I do that? I had no idea, I didn’t know anybody. But I thought that maybe I could write a book, because of course you need talent, but you don’t need to ask anybody for a job, you only have to write your book. And if it is any good it will be published. It seemed to me it was an egalitarian art. It didn’t matter who your father was or how good-looking you are: if your book is any good it will be published. I really believed it and actually still believe it. My first book was sold without an agent, I sent it up to New York, it landed on an editor’s desk, he read it and bought it. One publisher.

One chance in a million.

I don’t know if that happens anymore, this was in 1992 and they still looked and edited submissions. It worked for me exactly the way I thought it was going to work.

You said that you adopted your worldview from all those movies you watch and, as we said earlier, these movies tend to show masculinity, friendship, loyalty… nut I guess there was also a lot of redemption, which is something I adore from your books. Many writers think that if a book ends badly it’s more faithful to reality. But in life there is redemption and sometimes things end well.

I can always tell when, I call it dilettante nihilism, when somebody is trying to be so dark. I hate nihilism, I feel like there’s always hope at the end of the day. Redemption can take a lot of forms, it can even take the form of death. You look at The wild bunch –which to me is the one of the greatest works of the 20th century- and the ending of that film is about their redemption through death. And the fact that they stay together, they are loyal to one another and they want out together is a positive ending to me.

Some years ago I interviewed Richard Price, and I see him as a very similar writer and personality to you.

We are friends.

He is also very partial to redemption.

Richard Price was a big influence on me. Clockers to me is like The grapes of wrath. If you look at what I was doing before I read that book it’s different what I’ve been doing since. I read his book and I thought that crime novel could be something bigger than what it was; it’s OK to push it and try to talk about larger issues within the context of the crime novel because he did it. He was a huge influence on me, but not only on me, also on David Simon. The wire wouldn’t be The wire without Clockers. And there’s a reason why Price worked on that show, we went after him. So yes, he is a big influence.

I think he has the same worldview, people make amends for their mistakes, for example in The Samaritan.

Yes, sure. I love The Samaritan, by the way, it’s a great book.

Do you think that redeeming oneself nowadays in the real world is something possible?

That’s what my book The turnaround is about. It’s based on a real event that happened in my teen years, when white kids went into a black neighborhood. They tried to drive back, but one of them was shot to death and the other ones were beat up. The whole basis of that book is that I wonder what happened to those kids, the white ones and the black ones, 30 years later. And is it possible for them to be redeemed. That’s what the whole book was about. If you look at The way home, which is another book I wrote, it’s about a kid that goes to prison and how he and his friend put their lives back together and how they come back and make it right with their families and so on. And that’s something you can find in many of my books, so you could say I’m a little obsessed with that.

Many people define your books as moral tales, and in a way I tend to agree. In The wire, for instance, there is no judgment, but in your book there is some condemnation, judgment and punishment. You favor work ethics, family ties, kindness to children and loyalty, and you condemn and punish the wicked, so it is moral.

David Simon and I have a difference. I was always pushing for that sort of thing in the show, but David had another idea about things. But the one character that I am not interested in getting in there myself is Cutty, the guy who comes out of prison, whom they try to get back into the drug game but he resists and he opens up a boxing gym in the city to help kids. He is one of the only characters in the show that hasn’t really a good ending. Because I believe in that. I’m active in prisons and guys coming out of prisons, and to me that’s a very important thing to support and to believe in, that there is a second chance. And people do change. And they change for the better. So I’m very much behind that whole ethos.

I interviewed Steve Earle and he started insulting Cormac McCarthy, saying that he bums him out because he is very depressing and has a very negative outlook, so he hates him.

Steve is a very good example. He was in prison, was a heroin addict… and look at what he is now! We had him on Treme. In fact, I wrote the episode where he got killed. But he was happy, though. But he is right, if Cormac McCarthy really believes the stuff that he writes about, that whole idea that there’s no hope and everything ends up in death I don’t know how he lives his life, really. He is a good writer and I enjoy his books but surely it’s not a philosophy that I subscribe to.

You talked about music, and we mentioned Richard Price. He told me that he was not that much into Motown, but more in the Stax-Volt catalogue and Southern gritty and R’n’B. Somewhere you described the way you saw somebody’s oldest sister dancing with abandon to Whole lotta love…

I’ll never forget that, man, I can see it now. I walked into my friend Charles’s, she was up in her bedroom and I could see from where I was. She was wearing just a bra and panties and she was dancing to Whole lotta love, that middle section where it goes off the rails, and I thought: “OK, this is what it’s all about, man”. Because rock’n’roll was all about sex. When that came out I was probably 12 years old and the whole thing hit me at once. That song and looking at her: this is where I wanna be.

This is where the good part of life starts.

Exactly.

Do you still listen to songs and feel them with the same intensity?

I do. I think that music is the one thing that consistently makes me happy and takes me someplace else. When I want to go someplace else I put the headphones on. It has the power to really move me in a way that most other forms of art don’t. I can look at a painting and feel something, but never in the way that I feel when I hear an Otis Redding song, or some of the rock that I love, like the Drive-by truckers and all those bands that really get me off. It lifts me off, it’s like a rocket. I still feel that way, I listen to music all the time; it’s a constant in my life.

I know you like Curtis Mayfield. Do you ever feel, listening to his Roots, you wish you had been born with that talent instead of the talent of putting words on paper?

You may know that Curtis Mayfield is my favorite of all time, he is my hero.

I didn’t know it, I just knew you like his music.

Just what he did in his time… People don’t realize that he was so brave, to be singing the thing he was talking about in a time when people didn’t want to hear about that, they didn’t want him on the radio because they just didn’t want somebody doing that, but he did it in a positive way, it wasn’t a hateful or negative way. He was always about “up with”. Roots is a great album, and the Super Fly soundtrack to me is one of my desert island disks, I can never be without that record. Or Back to the world… all those string records are just incredible. The one called Curtis, which is the one with him in a yellow suit in the cover… To answer your question, I have some musician friends, and they tell me they wish they could write a novel. But dude, there is nothing more that I would want to do in my life than to be in a band. When I go to a show I am the guy standing in front of the stage with my mouth wide open, mesmerized, because I can’t do that, and I would love it.

If they gave you the choice now, would you rather have been in The Clash or write a novel?

Of course, to be in The Clash, it’s an easy answer.

Family relationships, especially fathers and sons, are another constant in your novels. In an article for The Guardian you wrote that when you were with you white afro face, ripped Levi’s and Pumas dancing to Don Cornelius or Curtis you must have been a terrible disappointment to him. Do you think you were really a disappointment? Have your sons been a disappointment to you?

You have to remember that my dad was other generation, he was a marine in World War II, very straight, and then they have this generation of kids who have long hair, smoke weed, rip jeans and all that stuff. I think that definitely, he didn’t understand me. And, how could he? It wasn’t his fault and it wasn’t mine, it was just a huge chasm between generations at that time. What happened for me was that when my father got sick I had this opportunity: I stepped in and took over the business. I dropped out of college, basically, and doing that I saved the family, because my parents would’ve lost the business, the house and everything, they had no insurance. And I didn’t take a nickel, I would empty the register and I’d bring all the cash home and give it to my mother. After that -and I was pretty young still because I was 19- it didn’t matter what I did, I was still the wild person that I was, I was staying out drinking beers, smoking weed… I was still that guy, but my father looked at me with different eyes. He didn’t care what I did, he respected me. So I had an opportunity that a lot of sons don’t get to have: I got to prove myself to my dad. And so henceforth I have the same problem with my sons, I want them to be more aggressive in terms of gaining knowledge, work… all the stuff that I believe in. And they are coming around. My older son is working in the film business, he is in a TV show now, and my other son works at the baseball stadium, he runs a world food place. I’m proud of them, because there was a time when I was just like my dad; I wondered what was wrong with them. There is something I talk about with my friends. I grew up with a bunch of guys like me: Italians, Jews… they are all immigrants or sons of immigrants, and they all did very well, in one way or another. And we talk a lot about this thing: if you have money, what can you do for your children? It’s ridiculous to pretend that you don’t have money. They don’t have the same motivation that I had, because I wanted to start working so I could buy things for myself because we didn’t have any money. So what’s their motivation? Why do they want to leave the house? There’s air conditioning and a big screen TV, so what’s their motivation? so I try to remember that and I confirm that it’s my fault because I gave them all that, but I can’t pretend that I didn’t do well, it’s stupid.

But your example is almost heroic. I have read about you filming The wire and then driving back home three hours every evening.

I wanted them to see me every day. I turned down a lot of work in those years, anything that took me away from where I had to be. Until Treme, when they were grown [his kids] and then I went down there and I lived and had an awesome time. I loved living in New Orleans, you should go there, it’s the greatest city in the States, it’s so much fun.

You always go into extreme detail in your books, not only about the music but about the looks. In your youth you must have been like a peacock, choosing very carefully your wardrobe.

Yes, I was really into it. I had a job selling women’s shoes, so I got into shoes big time. And to this day, when I see a woman the first thing I look at is her shoes, because if she is wearing a nice pair of shoes I know that she cares about herself. That was the best job I ever had, selling women’s shoes, because I was a young guy, I was talking to women all day long, I got to touch their legs and their shins… it was awesome. Now it’s not like it was anymore, I don’t have a lot of things, but the things that I have are nice. I like to wear nice Italian suits, I wear Hugo Boss shirts, I am very particular about my shoes and I think it’s really important to look a certain way when you leave the house.

Do you still believe that these are important things, as much as when you were young?

When you have kids things change. And when your kids grow up you are going to change again and you are going to go back to a lot of things that you had close to you when you were younger, because you don’t really change, the situations change. You are still that 19-year-old guy walking down the street all cocky. You are still that guy. That doesn’t leave you.

That’s the most beautiful thing anybody has ever said to me, thanks. Regarding your passion for cars, Harry Crews wrote the book Car, which is about someone trying to eat a car. Some years later he said he was ashamed of having been so obsessed by cars, and thought that the cars were an evil thing. Do you still love cars, or the same that happened to Harry Crews happened to you?

I still love cars. Do you know the movie Bullitt? Have a Bullitt Mustang in my garage, it’s a replica of the car. It’s a very limited edition. And it’s my pride. It’s a beautiful muscle car. My first car was a 70 Camaro. Then I drive a jeep for my every day drive because I need something for my Kayak and my bike but if I had room I’d had a bunch of cars. Unlike Harry Crews, I’ve never turned my back on cars. I don’t know what he is talking about, I think it’s a very American thing. I was talking to Kevin Powers last weekend, a young writer. When he got his advance money for that book he bought a Dodge Challenger. He is living in New York. He said that NY is a great city, you can do almost anything, but the one thing you can’t do is having a car. For guys like him and me that’s a deal breaker. I need to get in my car every day and drive. If I lived in New York and didn’t have a car so I had to take subways and cabs it would be a big piece out of my life. I would feel that something is missing.

From our perspective, Europeans born after World War II, America can be a place a bit dangerous to live in. I’d like you, as an American who has lived abroad and has seen many other countries, to tell me: Is it such a dangerous place?

We certainly have a problem, with guns, especially. It’s not something you think about every day, I certainly don’t. My family chooses to live our lives. It’s better to live your life unafraid and deal with whatever comes up, but it’s something we don’t think about. I have been all over the world and I have to say that’s a nice aspect of your life over there in Europe, you really don’t worry when you walk around. I’m sorry, it’s not that great an answer, but the answer is that it’s something I don’t think about anymore. Because I’m here, this is my country and I’m used to it.

Translated in collaboration with Nicholas Elliott

Pingback: George Pelecanos: «A veces la violencia es necesaria, es catártica»