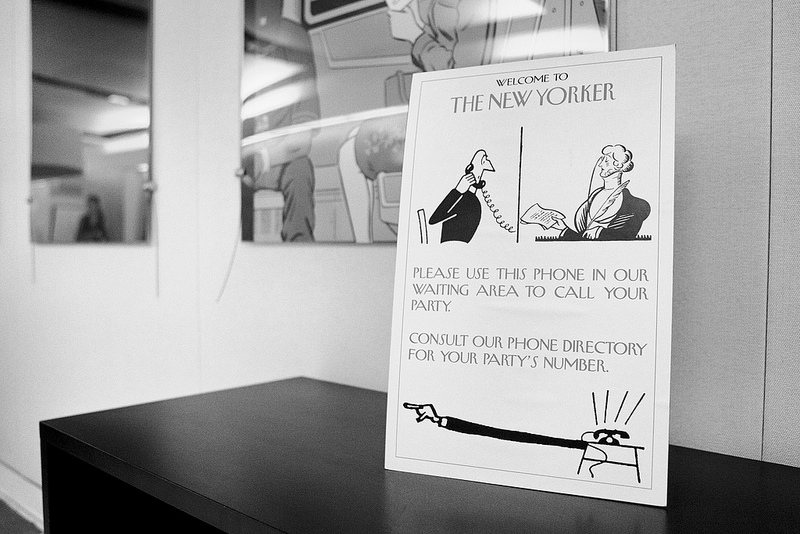

The New Yorker is a temple of good journalism that manages to endure in the middle the economic and talent crisis that ravages the sector. The New Yorker, even in tough economic times, is a profitable magazine, and Remnick’s strategy is to thrive in the internet age by investing both in the new means of distribution —the web, iPads, etc— and by continuing to invest heavily in the things that are most important: the writing, the editing, the fact-checking. Just as it has always done. Its celebrated facts checker, the department that verifies the veracity and rigor of the writings, even of the interviewees’ quotes, is as effective as always and has expanded to the internet. David Remnick has been its editor in chief for 15 years. Although he is closer to 55 than 54 he looks young, has barely any white hair, and does not wear a tie. He worked as a journalist for the Washington Post and as foreign correspondent in Moscow. He witnessed the dismantlement of communism. As I was walking into the editorial department, located at 4 Times Square, I run into Nobel Prize winner Wole Soyinka, who had just delivered an article or agreed on the following. These are extraodinary occassions. Remnick’s office stands among skyscrapers, full of light, without ostentation

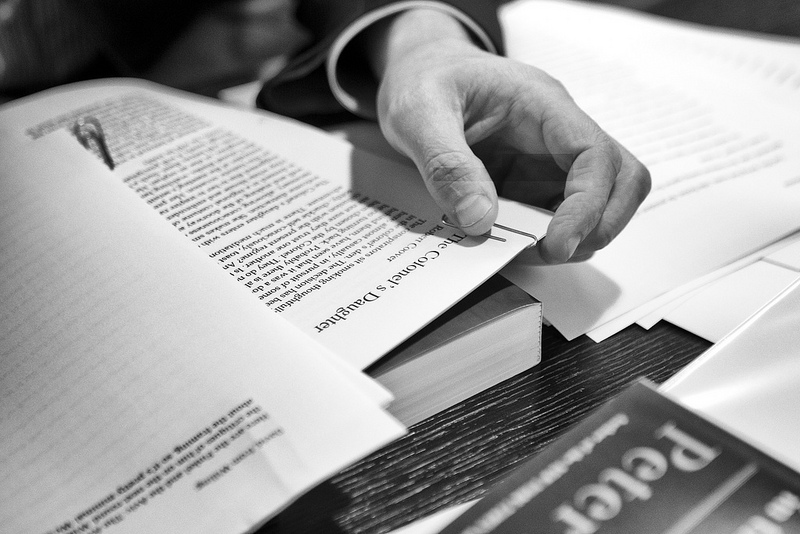

It all began a few weeks ago, with an email and a request for an interview. There were several conversations before anything was settled. One morning at the beginning of July, when I was already in New York, I made a last and desperate attempt to contact him. He replied right away: “Can we meet up today at 2.30 pm?” . The meeting did not start well. It bothered him not having been told there would be a photographer, but he was already acquainted with my biography and with Jot Down’s website. He likes to have all situations under control. After a few quick pictures, sitting alone at the table and before some bottles of water, Remnick finally relaxed. No one interrupted for almost 50 minutes. His cell phone rang, but he did not answer.

Everyone is talking about the end of Journalism; what do you think about? Do you think it is true? Are we approaching to its end or, on the contrary, only some of these companies that are now doing journalism are going to disappear?

Well, it is almost indecent to talk with somebody who has gone through what you’ve gone through and then saying “no, it is not going to end”. But I think that’s the truth. Of course it’s not going to end. Journalism is a very old and essential human activity. Without it we’re screwed, really, screwed. And maybe The New York Times is imperfect and The New Yorker is imperfect; the very best institutions are radically imperfect, but without them we’re screwed. Why? Because without Journalism there is no pressure on power, except for the occasional elections and in that case, without Journalism, elections would be even more… Uninformed than they already are.

So I think it’s demanded, and demanded of us. But we’re going through a gigantic technological tectonic shift, and as with every economic and technological shift, there are consequences for the better, and then unintended terrible consequences. In some ways Journalism now is better and in some ways it is worse. It’s very clear. It’s better because it’s immediately distributed. If I want to read thousands of things immediately I can now do it, this is the “now”.

My ability as a journalist is now enhanced by technology. When you and I were younger men and we were filing from the field, it was impossible to file from Armenia during an earthquake, from Turkmenistan or the many places that you’ve been. You didn’t, you didn’t file it all! You wrote it down and then you got back to the capital, and then you wrote it and then… Now there is not technological excuse for not being everywhere. We could talk about this all day and bore everyone because maybe you and I are more interested in it.

What I wanted to say is that no, I don’t think it ends, but clearly the unintended consequences are brutal. For example, I begin my career in the most wonderful way: I get a job immediately at The Washington Post. This is like a blessing. The Washington Post in 1982 or 1981 when I was in my early twenties was amazing. You should have seen us! It was the post-Watergate glory, and I was making all kinds of money. All kinds of advertising market city were tapped into and that meant fundingfor reporting, national or foreign reporting. Now, I pray for its survival. Its survival! And this is The Washington Post, not The Sacramento Bee or The San Jose Mercury News. This is an essential, a seemingly essential institution. You come from Spain, the reputation of El País, is international. When we begin to think that El País might be endangered, where will be Spain in terms of the quality of its information and Journalism? It’s, and most importantly, it’s pressure on power.

But we’re now in the middle of this uncertain situation, most of the people say it is caused by the general crisis, and it’s clear that we have all made many mistakes, especially in terms of understanding how the Internet could help us doing our work. How would it affect us.

This is all true and it’s easy to see in the rearview mirror. It is easy to now look back and say “we should have done this, we should have not”, but if you look at it in real time, some of these so-called “mistakes” are very hard to see. For example, in Washington everybody criticizes The Washington Post for not buying Politico.com. First of all, I have my very next view of Politico, that’s political reporting. But we’re not talking about that. The Washington Post had a website, they reported on politics and had invested heavily on it. So why should they buy Politico? I understand completely why Donald Graham made that very bad decision. And I don’t think buying it would have solved it at all. Maybe it could have helped The Washington Post, but they would have needed to face the crisis anyway. I’m sorry, but is Politico making a lot of money? No! Is Huffington Post making a lot of money? No! Lots of these things that have a big reputation and internet success aren’t making any money either.

Coming back to the first topic of our conversation, how can we convince people that Internet is not enough to be informed?

I don’t agree with you. I think the Internet is just a tool, a means of distribution. And it’s a radically more efficient means of distribution than print.

But some people may have the impression they can know everything what is happening only with a click.

And they can. If they buy things on the Internet. In other words, The New York Times can’t be for free and I have no problem with people reading The New Yorker online. I’m 54 years old, you’re 58 and we may prefer it printed for all the reasons that all the people prefer things that they are used to. I prefer certain kinds of drinks, I prefer Bob Dylan to the latest hip hop sensation, but that’s because I’m 54, that’s nothing, that’s just an ordinary normal human being.

What I want to say is that you can be beautifully informed with nothing but a laptop, but you need a laptop and a credit card. Because it can’t be for free.

And do you think people are ready to pay or it is too late?

Yes I do. They are only prepared to pay, and this is the secret of what I think is The New Yorker’s success in a long term, if the quality of the information, or the writing, or the Journalism is markedly better than, more accurate than, more beautiful than the stuff that’s everywhere like water. That’s for free. So, if The New Yorker is just a name and the quality of the journalism goes down so it’s not better than anything else, then of course they’re not going to pay for it.

My strategy, both morally, financially, and journalistically, is to be even better than we were when there was no such a thing as an Internet. To insist on constantly pursuing of quality, higher and higher, which is expensive, by the way. And hope and pray that people will pay for it. And they do.

How is the crisis affecting The New Yorker?

Well, it is not just the crisis. This enormous change we’re going through is a big opportunity too. I was in Barcelona the day before yesterday. I was online. I read The New York Times, I read The New Yorker. Rather than struggling with my non-existent Spanish over a copy of La Vanguardia, El País or something else, I read a lot of other things. Immediately! And that’s very good! I mean, maybe I should learn Spanish, but that’s another issue. That’s another issue.

That’s an incredible thing! And you may be against somebody reading the newspaper or websites on their telephone, but, forgive me, that is just you being … old. Like me. Maybe you are used to a cup of coffee and opening the paper, and then the whole reading. That’s ritual, that’s not journalism. We all have our rituals, a bathrobe, a pipe, a cigarette, a cup of coffee… but that has nothing to do with journalism.

Considering the enormous amounts of available data on the Internet, what could we do to keep the quality of the information?

First of all, let’s not to be romantic, overly romantic, about the uniformed brilliant quality of all Journalism in the pre-internet age. There was a lot of crap, either sensational, inaccurate, unfair, banal, stupid, pandering…Let’s not be overly romantic and pretend that everything that was ever printed, in print journalism and everywhere, was the quality of Watergate or The Pentagon papers. Or the best of Orwell. It’s just not true.

So let’s not be absurd about the quality of all journalism before the Internet, as if we were all golden age brilliant work. Let’s be focused on technical advantages of the instrument, and technical advantages of the innovations that are available. Both in the doing of journalism and in the distribution of journalism.

You know? In the end, our biggest concern is the financial model, that nobody has completely figured it out yet. The New York Times, and other places including The New Yorker, have a paywall. People have to pay. And it’s not cheap.

One of the most terrible things, in my opinion, of our time is the diminishment of foreign reporting, at least in American journalism. It’s severe. Severe. And therefore, the few places that still do it receive an enormous pressure. I remember when I was in Moscow, in my late twenties. Obviously the story was bigger. Now, there is hardly anybody there and the bureaus are much fewer. How often do you see foreign stories, with real reporters on the ground on American television? They get away with this as little as they can. And there are some superb correspondents, brave correspondents. People who know languages, but the amount of the time they get is very little. If you go on CNN, you’re not going to see a lot of foreign stories unless there are 2 million people on Tahrir square. You are going to see a trial, you are going to see all kinds of nerd kidnap, you’ll see all kinds of junk before you’ll see a foreign reporting. Anyway, this is a long, long conversation, but it is too bad.

How could you describe The New Yorker in terms of identity?

Do you know the old Louis Armstrong story? He was asked to define jazz, and he answered, “If I had to, If you don’t know, I can’t tell you. You have to hear.”

The New Yorker is a very strange, beautiful, unique mix of things. It doesn’t exist in other places of the world, and I’ve looked everywhere, the particular combination of things, of humor, deep reporting, fiction, and cultural criticism. That mix and that level of ambition are pretty unique. It’s only in English speaking world. I can’t pretend to know every language around, but I’ve seen somebody imitated it in another language, Chinese and Russian for example, and they never succeeded; it’s a very strange animal. Very strange. It’s like one of those creatures in the Museum of Natural History. But thankfully the animal is alive and well.

Talking about the combination of elements. I think the key to success is combination plus luck. And, of course the moment is very important too.

The luck began in 1925 with a man called Harold Ross who by the way was not a tremendously intellectual figure. He was a kind of crazy, interesting newspaper man from the midwest, who had this idea and developed it to become what it is.

What is the relation between the magazine and Internet? How is the famous facts checker of The New Yorker reacting?

I’m having a meeting tomorrow, literally tomorrow, in which we will decide that part of our enlarged budget will be used to add a facts checker for the Internet.

A website has to be fast, it has to be reactive. We can’t apply the same amount of time to all kinds of information we write, we cannot compare the time needed to write a short blog post with the time needed to compose bigger reports. On the other hand, you can’t just put any piece of crap that comes into your head online, because then you undermine the whole project, what The New Yorker is. Our website has to be an organic link between what is in the print magazine, which is by the way also partially online, and the things that are online only. Because it’s very obvious that after time these things are going to come together, and more and more readers who read their whole experience of The New Yorker will be either on the laptop, or on an iPad.

You live in Spain, why should you subscribe print version? It will take you two weeks to get it, maybe one if your mail is good. You can now get it on your iPad the second that I get it. That’s kind of great! And I hope the experience of it, not only is the same, or similar, but there’s also extra things to go with it. You can hear the poet reading the poem; you can hear the short story writer as being asked questions about the story. For me, the opportunities are immense.

I share with you all the anxieties, how can I not? But at the same time there’s a tremendous potential opportunity. My anxiety is not only for my friends, who I see in trouble. I grew up in New Jersey, right across the river, where there’s a newspaper they call The New York Star-Ledger. Every mayor of New Jersey, except the present one, has gone to jail, that I remember. Every single one. Who sent them to jail? Usually the newspaper, or at least it began with an investigation. If that newspaper, which is a medium size newspaper, shrinks to nothing or goes out of business, God forbid it, who is going to send the major to jail? Who? His assistant? His chief of staff? The judges that he appointed? The police that work for him? Are they going to send him to jail? If he is a crook, if he is dishonest? No! So there are a million reasons why we need journalism of a highest level. Not the crap, not the Kim Kardasian, I don’t know the Spanish version of Kim Kardasian, but you have your own…

In Spain we have a gold mine.

Yeah, of course.

What magazines do you read, The Economist, The Atlantic, The New Republic?

Yeah, those, all those.

And do you think they’re going to survive too?

Yes, I do think so. I think a lot of it. In my opinion, if you’re really good and you make yourself imperative to your reader, then you are doomed to success. There will may be a lot of broken hearts and lost jobs on the way, there will be maybe a lot of people who will have to retire early, unfortunately, there will be all kinds of consequences that are difficult or ugly or unexpected, and there’s no guarantee of anything. There’ve been many great things in this life that have died when we didn’t want them to…

At what time do you get up in a normal day? What is the first thing you do right after it? You switch on the laptop? Maybe drink some coffee? Do you read the papers?

I usually get up at 5 or 5,30 and I don’t use the laptop. Sometimes I’m tempted to go look at my email and make sure nothing terrible has happened overnight, or even good, but usually I have a cup of coffee and I go get some exercise because I hate it so much that I want to get it out of the way.

You watch morning TV?

Nooooo. No TV.

How many hours do you work every day?

I don’t say this to show off or to brag, but I don’t quantify them anymore. I’m always thinking about it. I’m reading all the time. Work is not just something you do in an office, so I just change the location. I work here, then I go home, then I work, then I take a break, then I watch a movie or have dinner with some friends. It’s all the time.

What kind of movies do you prefer?

Well, let’s see what I have here. The autobiography of Ceaușescu, The man who knew too much, which is a Hitchcock…I take them home and I watch them in the middle of the night. You know these are highbrow things but I watch the latest Hollywood crap too. That’s my outside of work passion, movies.

Where do you find the time to write your books?

I don’t. During the last 15 years I’ve only written one book, and I did it all in one year and maybe three months. I did this ridiculous project, called “The Bridge”. It was an absurd project. I wrote essentially a biography, a kind of racial biography of Obama until he becomes President, and I did it all in an absurdly short period of time, and it’s not a very short book, I think it’s out in Spanish too: El puente? Is it that?

Are you happy with Obama?

It is not my job to be happy with politicians; it’s the opposite of my job. But I will say that considering the congress we have, which is the most right wing in my lifetime, specially the House of Representatives, including the Reagan years and the Bush years, I think he is a vast improvement over its predecessor, vast. But we don’t live in a parliamentary system, we live in a presidential system, which depends on opposition congress to compromise with and work with the President, and that doesn’t seem to happen very often.

I’ve read somewhere, I don’t remember if it was in Spain or in England, that we passed from “yes we can” to “yes we scan”. Obviously, it was related to the latest news informing about American espionage over its citizens. What do you thing about espionage, and more precisely, about the secret espionage of the population?

I play my role in society, and my role as a journalist is pressure on power, is transparency. I totally understand why the Government wants to keep secrets. I really do. I mean. In fact there’s a kind of secrets that should be secret. I know it’s not very fashionable to say this but if do think so.

I’m often in the position of publishing things that the Government wants secret, and we publish them anyway. So it’s not simple. If all responsibility for secrets and transparency is in the hands of Government, then the opportunity for abuse is obvious.

You wrote King of the world: Muhammad Ali, some years ago. Who is in your opinion the person that in this moment has the moral statute that once had Mohamed Ali?

Well, I have to say first that Muhammad Ali was not a political thinker. Let’s not exaggerate his figure. He was an athlete; he was a beautiful athlete, who was the champion of the sport most people don’t care about anymore in this country. I don’t follow it much anymore. I cared a lot more about Muhammad Ali than I did about boxing even then.

To answer your question I’d say that the obvious moral hero that is still alive is Mandela, who is a much more complex figure. I’ve been a huge admirer of him.

I have the impression that after Mandela we don’t have new “social heroes”. I think that perhaps the Aung San Suu Kyi in Burma could be one of these figures…

Yes, but her reputation will go down when entering the room of normal politics. That’s the prize. When you switch your role from the prophetic to the political then certain things can change.

Do you have normal friends?

If I have normal friends? I only have crazy friends.

There was a director of The New York Times who said “I always go out one day per week with normal people, no journalists, no politicians, so I can learn what people are talking about”.

In my case, of the ways that I get out of the office is I actually going out and report. Three weeks ago, the office was closed for a week and I’m not very good at going to the beach, so I went to Jordan and I spent most of my time inZaatari, which is a big refugee camp on the border of Jordan and Syria. I haven’t written the piece yet, I haven’t had time, but I’ll finish writing it this weekend. That’s what connects me to the world. I have friends I go out dinner with, I’m not a weirdo (laughs).

Is it possible to be a good journalist and at the same time be a good director? Everybody knows that many directors, who were once journalists, change a lot when they are promoted, being more interested in money than in people.

Maybe but a director knows that he is in charge of a big organization which also is a business. You can’t, I can’t afford reporting two stories in a year. If I were out running around the world I wouldn’t be doing my job. I’m responsible for The New Yorker week to week but also its future. I can’t indulge myself and try to be everything. You can’t do everything well.

My responsibility is to this institution and the people over there, and they don’t give a shit if I write a good story in Jordan or not, that in a way is pure self-indulgence.

But you continue writing…

But I don’t do it very often. I’m somewhat quick writer, I may not be very good but I write somewhere quickly, and I hope it doesn’t interfere whit what is 95%-98% of my work, which is the working as the editor of the magazine. That demands all my time.

I remember a report you wrote in Israel eight years ago. I tried to copy the idea it for El País. It started with a man, a friend of yours, Palestinian, with whom you were drinking some coffee. Suddenly, someone told him by phone that her daughter had been injured during a basketball match. At the time you were arriving to the hospital, a lot of people affected by a Hamas bomb were arriving too…That was the start of the report. In the end, the conclusion was that we can only make peace from the center, but there is no center or it is really, really narrow, so…

Yes Ramón, I remember the story. One of the things that has been my obsession and maybe yours too, journalists’ obsession in general, is non-fiction writing, how to tell a story that is true in its tale and it is also true in world history. That’s a very big subject. And I’m always disappointed when I learn sometimes that writers misuse one of them, or even both of them to get more spectacular results. For example, Ryszard Kapuscinski.I understand all of the extenuating circumstances. He is in Poland, he’s really writing about Poland while he’s writing about Ethiopia or wherever he is, but I think making up the tales, making up scenes, making up characters… there’s a word for that: it’s called fiction. And I have no problem with fiction, I love fiction, I read fiction. But don’t be a bullshit artist.

Non-fiction is its own art and there are masters of it. My hero, like so many other journalists, is Orwell, and I don’t say this because of where you’re from but Homage to Catalonia might be my ideal book. It may turn out there were details in it that he would actually slightly elaborated, I don’t know, I don’t know the history there. Anyway, that’s an old debate. But part of my job as an editor is to enforce this distinction.

Continuing with the same report you wrote in Israel, I had the impression after reading it that peace between Israelis and Palestinians was impossible for this generation because very few people are in the middle. And by the middle I mean people who respect the other side.

Well, on the other hand there are peace talks beginning today. I know the arguments for pessimism and I know the arguments for optimism but stranger things have happened, right? I lived in the Soviet Union at the end of the eighties; no one, no one in 1991 thought that Soviet Empire would reject communist ideology and collapse. No one. Not the CIA, not the American Government. No one. So stranger things have happened. And, you know, despair is the unforgiveable sin. I think the radicals are on both sides. They exploit people’s despair. And it’s … radically unhelpful.

It seems that everything is a mess. Syria, Lebanon, Egypt…

It is true. But everything is a mess everywhere! All the time. Almost everywhere. Except on a long weekend in Barcelona when I go out dinner and I pretend that life is what it isn’t. Because I’m in a nice hotel, and I’m going to bars and I’m having a nice time. That’s not life. That’s fantasy. That’s a lucky, lucky fantasy. How many places have you been in as a foreign correspondent?

I don’t know…many.

You’ve seen things that most people, thank God, don’t have to see. I think the worst kind of journalism is the journalism of prediction. Journalists who pretend to know the future, who go on TV and say “this is going to happen”. That’s usually full of shit. Full of shit. No one journalist, no one, could possibly have told me that in 1985 a man named Gorbachev with a spot on his head would appear and that intentionally or unintentionally, the Union would collapse. That a kind of half democratic-half drunk success would come along and do great things and horrible things. No one would have predicted that Putin would come along and reinstate a kind of, I don’t even know what to call it, authoritarian…In other words, the art of prediction is cheap. The art of accurate description, of analyzing what actually is, is much more difficult.

Do you think Putin has future?

If I think he has a future? Yes I do. Unfortunately. Of course I do, because the rules are on his hands. There’s no justice system, there’s no balance of power, there’s no tremendous journalism that matters. In a country that large without television…there’s no journalism. It’s just a few magazines that sort of tell part of the truth. They’re limited to Moscow and Saint Petersburg intelligentsia and that’s it.

And how do you see Spain? Are you following the latest news?

Well, my opinion is completely fantastical. I mean, I don’t know Spanish and I’ve only been to Spain a few times and for very brief periods. So I’m not a Spain expert, I’m really not. It would be foolish to make up an opinion.

If you were 25 again, how would you like your future to be?

You know Ramón? I’ve had a great career. Considering my professional life, I’ve been luckier than or at least as lucky as any human being I can name. I started wanting to do this activity from a very young age; journalists were heroes when I was an adolescent. I grew up in a small nothing town, and my job was something that would bring me into a larger world. And that’s exactly what it did.

Because I got lucky twice, professionally. I was hired as a very young kid at The Washington Post, and then I got sent to Moscow in the middle of the big story, in the post-war period, that’s one thing. And then, two, I came here and some great things have happened to me. I’ve been unlucky in life in other ways, but everybody is. And everybody has their tragedies and unhappiness.

What would you say to all of those students who want to become journalists in a time when the profession seems to crumble?

I would just say: “ Jump in If you have to do it, and then you’ll find the way”. I know it sounds like a very easy thing for me to say, but there are opportunities that may not sound as opportunities to you.

If I were 25 years old some editor 20 years ago would say, at least in my country, “go to some provincial newspaper, in New Hampshire or south Carolina or wherever, and work your way up”. But that was the old path. Now the path is through websites. If you can find a way to make a living, and find a way to write things that you learn from, that you are not ashamed of …then you have half way to a lucky life.

The biggest problem is making a living. That’s the difficult. Freedom is not the issue not on this country and not in yours. Thank God. We’ve blessed not to have that problem.

In my opinion, for magazines it is easier to work deeply into a story because they have more time to work than newspapers…What is your opinion about the delicate position of newspapers today?

Little by little, the best newspapers are discovering that they’re also partly a magazine; I’m taking New York Times or El País. We find in them longer pieces because I think they want to distinguish themselves with things that matter or have some lasting value. It is not just late, but there’s been a long period of time in which they have not reacted quickly enough. Now, some reporters of the New York Times spend months on stories. And then there’re people who write every day, because they are covering the City Hall, or The White House, or the State’s department, or a war.

What do you need to have long good reportages?

Firstly, you have to read everything, and spend enough time. It’s just time. Sometimes when I get somewhere after having read a lot about it, I think I know everything after a little while, and then if I stay longer then I know nothing. And that’s when the process of real accumulation begins. I think most people stop after the first step. They get there, they look around, they interview some people and they feel that they know what they need to know and that’s it. And for either financial reasons, or laziness reasons that’s where the process ends.

And Ramón, it’s expensive. To put journalists on a plane, to go somewhere, to hire a fixer, to eat, to stay there for a while, then coming home, then spend a few weeks writing, and then check, then edit, the edit, then edit, then edit….the whole process. It’s expensive.

Thank you very much, David Remnick.

Spanish translation: Carolina Camarmo and Miguel Carrera Garrido

Photos: Julio Gamboa

Pingback: David Remnick: «No seamos románticos: en el periodismo anterior a internet también había basura»

Pingback: Bitacoras.com

Pingback: David Remnick INTERVIEW | The Periscope

Pingback: Interview with Girish Gupta: the Power of Decisiveness | Make A Living Doing What You Love

Pingback: Interview with Girish Gupta: the Power of Decisiveness | Jean Guerrero, Journalist