(Versión en español aquí)

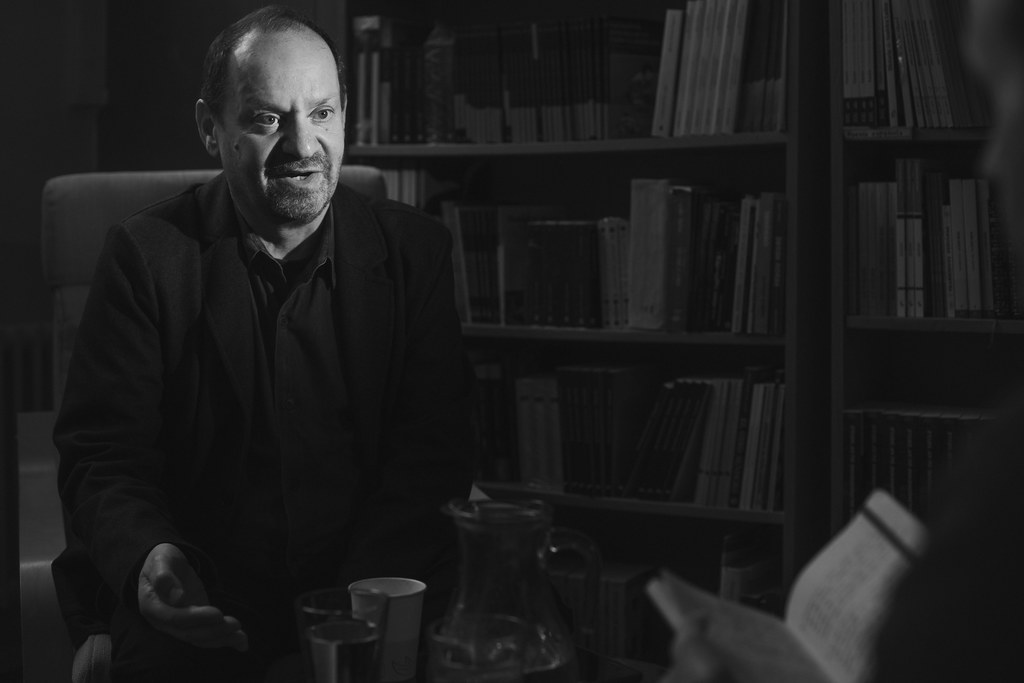

Philippe Sands (London, 1960) is a writer, university professor and international lawyer. He has been involved in cases concerning the war in Yugoslavia, the Rwandan genocide, the abuses in Iraq and Guantanamo, the indictment of Pinochet, the killing of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, the persecution of the Rohingya and, right now, the Chagos ilsands, among other prominent cases. He has exchanged with President Bashar al-Assad on the limits of his legal immunity as chief of State and argued against Aung San Suu Kyi in The Hague. Sands negotiated the creation of the International Criminal Court, and, not being satisfied with the four offences that underpin the modern system of international criminal law (war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and aggression), is now leading efforts to put a fifth crime in the Rome Statute, namely: ecocide.

Apart from his many academic publications on different international law issues, and from being a regular contributor to The Financial Times, The Guardian and Vanity Fair, Sands is the author of several essays, plays and novels, including East West Street and The Ratline. He is the president of English PEN and trustee of the Hay Festival. We seized the opportunity of his recent visit to Geneva to arrange a meeting at the Albatros, a cozy Spanish bookshop in the center of the city, barely four minutes by foot from Borges’ grave. Rodrigo, the endearing owner, welcomed us to his studio in the back room. The air of a worn-out world hardened the atmosphere. It no longer seemed right to start the interview by discussing Sands’ obsession with Nazi criminals, or his friendships with Javier Cercas and John Le Carré. We live in a different reality, which demands different beginnings:

Should President Putin be prosecuted for international crimes?

That’s something I’ve been working on. A couple of weeks ago, I was asked by The Financial Times to write an opinion piece on an aspect of law regarding Ukraine and Russia. For some reason these things write themselves, so I just started writing. I wrote a piece in two hours to call for the creation of a special criminal tribunal to prosecute the crime of aggression in Ukraine.

The next 24 hours were a little crazy, as I received hundreds of messages of support. And then Gordon Brown got in touch and said: “Let’s do this”. And for the last ten days I’ve been working on creating one. So I think it is an idea that may happen.

After your article, you co-signed a statement calling for the creation of this Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression Against Ukraine. Other signatories include Gordon Brown (former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom), Benjamin Ferencz (former prosecutor at the Nuremberg Military Tribunals) and writers Paul Auster and Javier Cercas.

It’s a real coming together of the legal world and the literary world, a connection with many of my friends.

What are the odds of seeing the creation of this court?

If you had asked me on the day I published my article, I would have said zero. A week later I would have said: ten percent. But after my phone conversation yesterday with various legal advisors of governments, I’d say thirty or forty percent. It’s definitively going up.

And the odds of President Putin actually being prosecuted?

That’s a different matter. A number of countries that we have been talking to have asked “what about Head of State immunity?” My answer to that is that it is a real challenge, but it should not inform the question of whether to create a body to fill the gap left by the absence of jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court on this issue. It will have to be addressed at a certain point.

The model we have taken is 1942: it’s a delegation of the domestic criminal legislation of Ukraine, which mirrors the domestic criminal legislation of Russia because, amazingly, both countries have in their domestic law crimes against peace (the crime of aggression) taken from the Nuremberg Statute. Guess who put it in the Nuremberg Statute? The Soviets. Aron Trainin, a very distinguished Soviet jurist, was the one who persuaded the British, the Americans and the French to put it in. So it’s a nice point of connection, and of irony.

I want to ask you a couple of questions later on about your friendship with the British writer John Le Carré, who passed away less than two years ago. But first, let me ask you a non-unsolvable riddle: what do you think he would have thought about the events of the last two weeks? Would he have feared a reenactment of the Cold War, or even worse, of the World Wars?

I think he would have been furious with the performance of the West. In the sense of not having thought through the embrace of Ukraine in a way that was really going to upset Russia. I’ve been to Ukraine about twenty times in the last twelve years. I was in Kiev and Lviv in October. And I always thought Ukraine should not be in NATO. It’s a transition country. It points to the East, it points to the West. It has a special situation. And I think the West has not played this well and that, in a certain sense, it was predictable. But that in no way justifies the horror, the barbarity of Mr. Putin.

Once past Le Carré’s initial state of fury, a lot of this would have been very familiar for him. The duplicity. The double standards. The things that are not quite what they seem. And he would have been taken back to the world he grew up in the 1950s.

Talking about duplicity and double standards: In Lawless World you argued that the Bush Administration, with the support of Tony Blair in the UK and Aznar in Spain, contributed to undermine international law. In what way was the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the West different from the invasion of Ukraine by Putin?

My views on Iraq were very clear at the time, and they are clear today. It was illegal. Period. I joined those who said this was an act of aggression. And I think people are entitled to say it’s a double standard to call on the creation of a special tribunal for one but not the other. But frankly, it should also have been done for Iraq. And there’s a certain irony that I’m now working with some people who were involved in the war in Iraq [like Gordon Brown]. I think a lot about that, but two wrongs don’t make a right. Iraq was wrong. Ukraine is wrong. And perhaps twenty years ago we could not have imagined the creation of a special criminal tribunal. Right now it seems that things have moved on and we can imagine it and agitate for it. It’s the power of words and ideas –I am inspired by legal thinkers like Lemkin and Lauterpact who, as I wrote in East West Street, did not curl up in a corner and weep. They reflected on the power of the law, and on words, and thanks to them we have genocide and crimes against humanity in our legal lexicon.

The International Criminal Court just came into being in 2003. The Rome Statute had been adopted in 1998, but it didn’t come into force until 2002. And it didn’t yet have jurisdiction at all over the crime of aggression. Of course, what happened subsequently was that the crime of aggression was codified in the Court’s statute, but not in a way that could be used in this case. There’s no jurisdiction over that crime in this case.

But the simple point is that I am extremely sensitive to the concerns of certain countries, particularly from Africa, who have been asking: “why all of a sudden so much attention to criminality, and to illegality, when twenty years ago you guys did the same thing?”

The recent vote in the UN was very interesting. Half the countries of Africa abstained in the vote [against the invasion of Ukraine by Russia] at the General Assembly. That says something.

I know we’re in the realm of speculation, but do you think President Putin would have invaded Ukraine in 2022 if President Bush had not invaded Iraq in 2003?

Putin actually cited Iraq in a television address that he gave. I mean, he cited lots of things. He mentioned international legal principles, including genocide being perpetrated in Eastern Ukraine. One of the things that was interesting for me was that this was a lawless act embracing the language of the law to justify the unjustifiable. Iraq gave Putin an easy justification. A wrong justification, in my view, but an easy one.

In Torture Team, one of your earlier books, you described the role of lawyers in authorizing the so-called enhanced interrogation techniques, which you, as many other international experts, have considered an alleged violation of the prohibition of torture under international law, including the Geneva Conventions. Tell me about how you researched for this book.

Until that point I had only written academic books. I was very proud of all my academic books, whether they sold ninety copies, a hundred and fifty copies, six hundred copies. And then, in late 2003, I went to a dinner party in London with a very dear friend, who is also the woman who introduced me to my wife. My wife’s father was a publisher, André Schiffrin, and one of his authors was the historian Eric Hobsbawm. And Hobsbawn’s daughter, Julia, is our friend. She match made us, with my wife, but she also match made me with the woman who became my publisher at Penguin: Margaret Bluman. I sat next to Margaret at the dinner table, and you know, you’ve had this experience, when people ask you what you do, if you say you’re a lawyer, people usually answer with an “Uh-oh”. But I said “well, actually, I do law that is sort of pretty interesting: nuclear weapons, bombings, mass murderers, environment”, and then we started talking about Iraq and Margaret said: “you know what? I think there’s a book in there. Send me a 10-page proposal and if you can write, I’ll publish it at Penguin”.

So that was the first step towards a bigger audience. I spent a lot of time on this proposal. She liked it and she published Lawless World, which opened a completely new door. That book sold thirty or forty thousand copies, and after you’ve written academic books that sell six hundred copies, it’s nice to have a bigger audience. At that point I think a new project began, which was to leave the ghetto of international law and write about international law for a bigger audience.

Both Torture Team and Lawless World describe actions that might amount to international crimes. And yet, nobody in the Bush Administration was held accountable for the aggression against Iraq, nor for the allegations of war crimes committed in places like Bagram in Afghanistan, Abu Graib in Iraq or Guantanamo Bay in Cuba.

No legal accountability, but other forms of accountability. Tony Blair can’t walk in the streets of London. That is a form of accountability. Donald Rumsfeld never travelled outside the United States again. George W. Bush doesn’t travel outside the United States. So accountability is a multifaceted thing. I don’t believe that accountability must only be in the courts of law. It can also be in the courts of public opinion. Justice works in very complex ways.

The reputation of Tony Blair was trashed because of Iraq, and rightly so. He will never recover. He will always be remembered for Iraq, even though he did many fine things in Britain. Its tragic. He could have taken responsibility but chose not do so.

So do you think the creation of this Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression Against Ukraine might at least bring this type of alternative accountability to President Putin?

It could. I think it’s also, as some people have suggested, a sort of expression for those who were involved in Iraq that perhaps it was not the right thing to do and that the law needs to develop. But the way the law develops is exactly like this. If you go back to 1945, it was a sudden great leap. Who knows what will happen? There is a lot of energy for [the creation of this new tribunal]. It’s quite interesting.

You participated in the creation of the International Criminal Court. Lawless World opens with a quote from Honoré de Balzac: “Laws, like the spider’s web, catch the small flies and let the large ones go free”. Is this the problem of the ICC and, in general, of international justice?

Yes. I used that quote for the first time at the International Court of Justice in the first case I ever argued, which was on the legality of the use of nuclear weapons. And I think I used it in court, and then I brought it up in the book. The law must not be like that, but of course the law is like that.

Very interestingly, last week I was involved in a Zoom conversation with a group of fifteen former heads of State from central-Eastern Europe on this idea of a special criminal tribunal for Ukraine. And one of the participants, a former president of a smaller central-European country said: “You know what’s great about this? I always thought international law was for the little people, the poor people, the powerless people. Wouldn’t it be great if it was used for one of the most powerful ones?” And I think that’s what is at stake now.

Is President Putin a large fly?

Yes, as large as it gets.

I don’t know what his mental state is, actually, right now. I mean, I watch really attentively and it’s really interesting to watch his set pieces and his conversations with his inner circle. It is plain that there are people in the inner circle who are uncomfortable with what’s happening. The body language is fascinating. There is very obviously dissent in the ranks, and anxiety, and concern.

There has been talk about a purge in the Russian spy community. When I read about it, it actually made me think of you and Le Carré.

Yes, generals from the spy community. I think this will end up getting sorted out in Russia. It will be an internal thing.

Well, let’s forget about the current war in Ukraine. Let’s look back at Ukraine many years ago. In particular, let’s look at the west of the country, near the border with Poland, to a city that you know very well, called Lviv or Lemberg. When did you first go there? And why? And how did it change your life?

I went in October 2010. In early 2010, I received an invitation to give a lecture in the city of Lviv on the cases I took part in on crimes against humanity and genocide. I accepted the invitation once I worked out that Lviv and Lemberg were the same city. I wanted to go to Lemberg because my grandfather was born there.

I spent part of the summer preparing the lecture and discovered that the men who introduced the concepts of crimes against humanity and genocide into international law came from the University of Lviv, and the people there didn’t know that. I thought that was astonishing.

In East West Street you weave together the life of Lemkin and Lauterpacht with that of Leon Buchholz, your grandfather, and Hans Frank, a Nazi war criminal.

I didn’t go to Lviv intending to write a book. I went, and I took my mother, because her dad had been born there. I also took my son and my aunt. It was a very powerful trip. Lviv is an extraordinary place. It’s very beautiful. It opens up the imagination, because the inner city hasn’t changed since the 1900s. It looks exactly as it did a hundred years ago.

I came back to London and my then editor at Penguin asked me what was I going to do next, after Lawless World and Torture Team. And I gave him five ideas, and one of them was that I could write a book about this and he said: “Do that”.

So I started writing it and then, curiously, Penguin decided not to buy the book. Instead, the book was bought by an extraordinary editor in New York, Victoria Wilson, at Alfred Knopf. And I worked with her for five years on four different versions of the book because there’s a lot of information in the book and there was a real challenge on how to present the material. Victoria is an editor not only for non-fiction, but also for fiction, and she has wonderful writers. I give her the credit for the structure of the book, which I think is what makes it work.

A structure where you mix the story of Lemkin and Lauterpacht with that of your grandfather and that of the nazi Hans Frank.

I found this very very difficult. Firstly, because, as you know, in our [legal] world you don’t write about yourself. Nobody is interested in your family story. So I had never written about this in Lawless World and Torture Team.

If you go through the books, you begin to see that my voice changes. It’s indistinctively present in Lawless World. In Torture Team I begin to describe the role I had in finding the things I was interested in. And the fullest voice becomes clear in East West Street. It was Vicky Wilson who gave me the confidence to make the leap between Torture Team and East West Street, and fully speak in the pages of the book and include myself as a character. That was very complex, because all our training, in the classroom, as a university professor, and in the courtroom, as a litigator, focuses on not talking about yourself. You don’t include yourself in the story. So this was very complex for me.

At a certain point, about two and a half years into writing the book, I said to my agent, Gill Coleridge, “I’m finding this too difficult, but I’ve got a great idea: let’s do two books. One book about my family, and one book about the lawyers”. And she said: “No, what’s different about this book is that it merges both”. She was absolutely right, but I found the process extremely difficult.

Lemkin was obsessed with the protection of the group. The crime of genocide focuses on the intention to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group. Whereas Lauterpacht, on the other hand, focused on widespread crimes against individuals. You’ve said that you would rather go for a beer with Lemkin, but that you prefer the ideas of Lauterpacht. Can you explain to me your hesitance regarding the crime of genocide?

Lauterpacht’s idea is that we should focus on the well-being of the individual and protect the individual because he/she/they are sentient human beings and they have minimum rights. Lemkin’s idea is different. He thought people get targeted not because of what they’ve done as individuals, but because they are members of a group that is hated in a given time or place. So in order to protect the individual you must protect the group of which they are members. I understand and recognize the logic of that.

The difficulty and the fear is that the protection of the group as an idea, I worry, reinforces the very nature of group identity, and reinforces the sense of self-identification of one group and its hatred of another group. And so, I worry, intellectually, that the concept of genocide gives rise to the very conditions it is intended to prevent.

On the other hand, East West Street ends at a place with me recognizing the power of Lemkin’s idea at a mass grave in a town just outside of Lviv. I’m looking into a mass grave in which there are three and a half thousand bodies, including the bodies of Lauterpacht’s family and my grandfather’s family, and I feel a sense of connection because I’m part of that group. And so, in a sense, it’s the complex relationship between the instinct and the intellect, between the mind and the emotion. Intellectually, I’m with Lauterpacht; emotionally, I’m with Lemkin, and I think that is something that most people can understand. It’s linked to the struggles we all have between ideas and emotions.

It’s interesting that without the law faculty of this Ukrainian city, we might not have the crime of genocide or the notion of crimes against humanity. And we certainly wouldn’t have the International Criminal Court as it exists today.

I think you can say that Lviv as a city is a cradle of modern international criminal law. Two of the four existing international crimes have their origins in this city. And they are the two that resonate most powerfully. If you take a look at the newspapers of the world, you will see that most of the conversation is about crimes against humanity and genocide. The individual and the group. It’s not about war crimes or the crime of aggression. So Lviv, in this curious way, has instilled itself in our consciousness, and in the public imagination, and makes what’s happening in Ukraine today so very resonant when concepts of crimes against humanity and genocide are being talked about in the context of the Ukraine – Russia conflict.

Talking about central-European cities: have you watched The Grand Budapest Hotel, the film by Wes Anderson?

I have. And I like that film very much. I’m a big film watcher. That’s based, supposedly, on a book by Joseph Roth called Hotel Savoy.

Roth lived in Lviv. And I’ve been to his houses. He lived in a whole series of houses on Abbott Hoffman Street. I’ve been to all the houses that he lived in and taken photographs. It’s an absolutely amazing street. And the hotel I always stay in, in Lviv, is called The George. I stay there because it reminds me of Hotel Savoy. It hasn’t changed in a hundred years.

It seems that another of the influences of Wes Anderson to make this movie was The world of yesterday, the famous novel by Stefan Zweig.

Yes, which is the one book I give to everyone. It’s the book I cite the most to understand what is happening now, in Europe, in Ukraine, in our messy world.

You’ve also mentioned this book, and Zweig’s “sense of political moment and era”, as one of the main influences for East West Street. What is so unique about The world of yesterday, and how did it capture your imagination?

It’s not just the substance. It’s also the style of writing. I hadn’t mentioned this to Vicky, the editor, but, about three years into the writing, there was a moment when I felt things were beginning to work, and she said to me: “The style of this book reminds me of Zweig, who is one of my favourite writers”. So we talked about it. What I love about the way Zweig writes is that he strips all the emotion out of the narrative. He simply tells the story and lets you, the reader, form your own emotions.

He tells in his non-fiction writing what is going on, but he does not impose upon the reader an emotional response. It’s quite dry. He writes with incredible restraint. And I love that style. And one of the things I wanted to do with East West Street was to not impose my emotions on the reader and let the reader form their own emotions and intellectual conclusions. That is drawn directly from Stefan Zweig.

In East West Street you quote a poem of Kipling, for whom men and women of good will should have “leave to live by no man’s leave, underneath the law”. The main characters of your book contributed to strengthening the rule of law. And yet, we talk a lot about the existential dangers to our liberal democracies. Do we need more people like Lauterpacht and Lemkin?

Absolutely. History doesn’t repeat itself exactly, but it draws from its past, and what we’re going through now reminds us a lot of the 1930s. We’ve seen the rise of nationalism, xenophobia, populism and challenges to the idea that individuals and groups have rights in relation to the sovereign State. All of that is being questioned again, so we have to strive to protect it.

I tend to be quite an optimistic person. What’s going on in Ukraine, with Russia, is terrible, but looking on the positive side, it’s a wake-up call. We thought this was finished in Europe, and we’re learning it is not. For my children’s generation this is a really big shock; but it’s also a shock that has a positive aspect to it, which is: “Don’t take what we have for granted”. It’s not a given. People fought for it and lost their lives for it in the past. And people will fight for it again and lose their lives for it again, now and in the future, and that has, I think, shaken us out of our complacency, where we were heading.

I think what has happened in the last two weeks is absolutely dramatic in terms of political, social and cultural impacts. We can’t even begin to imagine what the impacts will be, but they will be enormous and they won’t all be negative.

We are in Switzerland and one of the things that is surprising is that Switzerland has decided to join the sanctions against Russia, in what, according to some people, is a change in its traditional policy of neutrality. For the country where we are, it seems like an important geopolitical change.

A huge change. And look at Germany: a hundred billion euros on rearming. It’s a huge development also.

I think it’s too early to know how this will all go, what the impacts will be, but we learnt that we can’t take anything for granted. We’ve had it very easy in Europe.

While you were researching East West Street you met Horst Wächter. And then you wrote an article about him in the Financial Times entitled My father the good Nazi. Tell me about Horst and your relationship with him.

Well, the relationship really starts with Niklas [Frank]. The real friendship is with Niklas, who is the son of Hans Frank, a man who was hung in Nuremberg for the murder of four million human beings. He wrote a book called Der Vater [The Father], which is a passionate letter of hatred by a son to his father.

I met Niklas because I wanted to know about his father. One day he said to me: “You know, Philippe, you are interested in Lemberg, would you like to meet the son of the [Nazi] governor? The son is called Horst, the governor was called Otto”. And I said: “Yes, sure”. And so we went to meet him, I think around late 2012.

I liked Horst a lot, but he was very different from Niklas. I’m fascinated by dichotomies. Niklas who hates his Nazi father, Horst who loves his Nazi father. Lauterpacht who likes individuals, Lemkin who likes groups.

Horst was totally different from Niklas. And the complexity about Horst is that he’s actually a lovely man, but what comes out of his mouth is often horrible. And this is complex. I’ve come to understand that Horst is a victim of that period. He was a little boy, and he struggled ever since to remake the world he grew up in as a little boy and to reconstitute the illusion that it was a great period. So I like Horst in many respects, but I don’t like what he says.

And the relationship with these two characters led you, in turn, to film a documentary with your friend David Evans, the director of Downton Abbey, called My Nazi legacy.

Basically, what you’re beginning to see, as in life, is that you open one door and something else comes up. You go to Lviv, you start writing a book about Lviv, then you meet Horst, then you write an article at the Financial Times, then somebody says “Let’s make a film about that”, and then the film becomes another book. The Ratline was not going to be a book. It was only a book because of the BBC podcast that followed the film. One thing led to another, and my whole world had been transformed by the single act of accepting an invitation to go to Lviv in the spring of 2010. Everything changed. Bizarre.

By the way, that invitation to go to Lviv originated in Switzerland. I went to the World Economic Forum in Davos and there I met a young Ukrainian lawyer from Ukraine. And I said: “Where are you from?”, and she said: “Lviv”, and I said, “Where is that?” I had never heard of Lviv. And she said: “Well, you might know it on a different name: Lvov or Lemberg”. And I said: “Ah, yes, Lemberg! My grandfather was born there”. So I told her I’d love to go there and find the house where my grandfather was born. She was responsible then for catalyzing the invitation to go to Lviv. So there’s a Swiss connection at the heart of it. I can indirectly thank the organizer of the World Economic Forum, Klaus Schwab, for East West Street.

Hence the set of coincidences that led you to your latest book, The Ratline, which has been compared to a spy novel. In reality, it is the extremely well-documented story of a prominent Nazi leader: Otto von Wächter, who happens to be the father of Horst. Can you tell me a bit about the story of Otto?

So I met Horst for the first time in 2012 and I’m totally fascinated by him. Here is a lovely human being who lives in this crazy Schloss, with no money; he’s totally broke. The first time I went it was minus two degrees inside the house. There was no heating. And then we started talking and he takes me up to the top of the Schloss and he’s got a library, and I put my hand in the library and I pick up a book and it’s from Heinrich Himmler to his father, a birthday gift, signed: “To the governor Otto von Wächter, with warm good wishes for all the good work you’re doing, Heinrich Himmler”. I was like: “Fuck!”.

But again, what happens is it opens up the imagination. I’m interested in this man. I’m interested in what his childhood was like.

How life happens is very odd. So I write the piece in The Financial Times and that piece leads to a documentary. In filming the documentary with Horst, there’s a moment where I interview Niklas Frank, and Niklas Frank describes Horst, in the film, as a new kind of Nazi. When Horst sees it, he’s very upset and says to me: “How can I prove that I’m not a Nazi?”, which is a sort of interesting question. I replied: “Well, I don’t think you’re a Nazi, but you’ve got all these documents” –ten thousand pages, which at the time I hadn’t seen– “why don’t you give them to a museum? Nazis don’t give family papers to Jewish museums, to holocaust museums”. And he said: “It’s a great idea”. So he gave an entire set of papers to the Holocaust Museum in Washington and then he asked me: “Do you want a copy?”, and I said: “Sure”. And it came in the post on one USB stick, with ten thousand pages of unbelievable documents. All in German, which I barely speak, and I start getting through the documents and photographs, which are incredible material.

Then I happened to go to the BBC and met with the director of programs. He wanted to commission me to make a three-part series on the future of international law. We talked about that and later on he asked me if I was working on anything else that was interesting and I told him about the USB stick and he said: “That would make a terrific podcast”. So we agreed we would make a podcast. That was early 2016. Then my editor said: “Oh my word, if you’re doing a podcast, you’ve got to write a book”. But it was podcast first, then a book. So one thing leads to another in a very very curious way. But the heart of it are the documents that Horst gave me, that I suspect he regrets very much having given to me. But it’s an extraordinary collection of documents.

When I read The Ratline I sometimes wondered whether the documents had been censored by Charlotte [Horst’s mother].

Definitely. I’ve said they’ve been filleted. It’s like when you take the bones out of a fish. She probably went through the documents and took out the most incriminating ones. Two years of diaries are missing: 1939 and 1941 or 1942. And we can’t know if the letters are complete, and if her notebooks are complete. My instinct is that they’re not and she went through them and took out anything that was really bad. But she didn’t do it perfectly. And that’s the wonder of the fallibility of the human spirit. She left some stuff in. Just enough to confirm the horrors. To confirm that they knew and that they supported the horrors. All of that becomes very clear in the correspondence.

You’ve also been accused of humanizing monsters.

I have no problem with that at all. Horst is human. Otto is human. Hans Frank is human. One of my favorite films is Downfall, the biography of the last days of Adolf Hitler. And that’s a great film precisely because it humanizes him. They are not evil monsters. They are human beings who did evil things. But they also have humanity and decency and the capacity for love and generosity. That is the reality of these human beings and to present them simply as monsters is wrong.

You have actually questioned the notion of the banality of evil, popularized by Hannah Arendt.

Yes, because the banality of evil thesis, as I understand it, is premised on the idea that the perpetrator was not really thinking about what they were doing and did not have agency. I think these people knew exactly what they were doing and embraced it. There was nothing banal about what Otto Wächter did. He was a complete and total true believer, as was Adolf Eichmann. We now know, from the book by Bettina Stangneth, the psychologist who gathered the correspondence of Eichmann from the 1950s, that he knew exactly what he was doing and supported it. So the idea that they were cogs in a larger instrument doesn’t work. They were knowing and willing participants. And I don’t buy the banality of evil thesis in relation to Eichman or Hans Frank or Otto Wächter. They absolutely knew what they were doing, they chose to do it, they wanted to do it, and embraced it. They were ideologically committed to what they were doing and they were weak people who were ambitious, and wanted to prosper. And for that they were willing to murder millions.

Last summer, I was at the beach reading The Ratline when a French guy next to me saw the cover of the book and told me he had read the book as a beautiful love story. You managed to do something amazing: a spy novel that is both a love story and an in-depth study of the human condition. Was this an unintended literary miracle? Or was it your plan from the very beginning?

It was my plan from the beginning, because, for me, the central character is Charlotte Wächter. She’s the most interesting character. She’s smart, she’s beautiful, she has passion, she is a Nazi, she is a champion skier, she is a true believer, and I’m fascinated by this human being. I’m fascinated by a wife who would spend three years climbing mountains for the love of her husband, to save him. It is absolutely a love story.

In fact, I’m very pleased The Ratline has just been bought by a German company to be made into an eight-part series. One of the things I loved about the German producer who bought it is precisely that she saw Charlotte Wächter as the central character.

Why is she so important? In all the stories that we work on, that you work on, it’s almost invariably violence perpetrated by men. Occasionally there’s a woman, but it’s very rare. But behind each of these men, there’s often a woman. And the woman knows, she participates, she is complicit and she condones. If you were to ask me what the key moment is in The Ratline, I would say it is when, on the 15th of March, 1938, Otto and Charlotte are standing with Adolf Hitler on the balcony of the Heldenplatz, and then they go inside and walk down the big marble staircase, and at the bottom of the staircase, as she records in her diaries, Otto says to her: “My darling, I have a choice to make: I can either resume my lucrative legal practice, or I can accept the offer of Arthur Seyss-Inquart and get into the [Nazi] government as a State Secretary. What should I do?”. And at that crucial moment Charlotte, the wife, the woman, has the capacity to thrust the family forever into a darkness or to save the family. And she thrusts the family into darkness. She’s the one who says: “I want the power”. She says it.

I never thought about the story in this way.

I don’t know. You have a partner; I have a partner. I speak to my wife about all the important things in my life. She saved me from some terrible mistakes. For instance, she’s the one who told me I should not represent Augusto Pinochet. If I weren’t married to her, I would most likely have represented Augusto Pinochet in 1998. Because she’s half Spanish, and in her family acting for Augusto Pinochet is like defending Francisco Franco.

But you had also expressed views about Augusto Pinochet’s immunity before being offered the case, right?

Well, I had to find a reason to get out. And yes, I had publicly, on the BBC, said that I did not think Mr Pinoceht should have immunity, because his alleged actions involved intrenational crimes.

So, actually, that was the excuse.

Yes, sort of. The real reason was the love for Natalia, my wife. My half-Spanish wife. Natalia’s grandfather was a Spanish soldier who defended Madrid for the Republicans, and in 1938, when they lost, he emigrated to England as a refugee. So the Spanish left and the Chilean left are big parts of the family life, and so the idea that Philippe, the husband of Natalia, would represent Pinochet was, shall we say, problematic.

Otto von Wächter was Hitler’s lawyer.

No, Hans Frank was Hitler’s lawyer. But Wächter did all the Nazi cases in Vienna.

But he’s a lawyer.

Yes, he’s a lawyer who entered the Vienna University Law Faculty on the same day as Hersch Lauterpacht. They were classmates. You couldn’t invent it. Fact is stranger than fiction. And twenty-five years later Wächter oversaw the killing of Lauterpacht’s entire family. And my grandfather’s family.

What I wanted to get at is the fact that so many of your characters are lawyers: the governmental legal advisors in Torture Team, but also Lemkin, Lauterpacht, Wächter… It somehow explains why your friend John Le Carré would come to your house with his manuscripts to check whether his lawyers looked authentic.

Le Carré hated lawyers. Every one of his novels has some horrible lawyer in it. And for the last eight novels, my job was to check the characters: were they accurately described? Do they speak like lawyers? Did they act like lawyers? And it meant I had to read the manuscripts. Because he would turn up at my front door…

You were neighbours.

Yes, he was our neighbor and we saw each other a lot. In the street, in the pub, we had lunch every couple of months or so. He would show up with paper manuscripts printed out at home and he’d say: “Usual procedure”, which was that I had to read through four hundred pages of printout and find the two pages with a lawyer. Because he didn’t put little stickies, you had to read the whole thing. But this turned out to be a brilliant thing, because I learnt how to create suspense.

From the best.

From the best. Literally the best in the world. How to make a reader get to the end of a chapter and want to carry on reading. I learnt his techniques. And one of the things he told to me was that he has huge respect for the reader. The reader is really smart. And the smart reader knows that a good writer has put every word, and every comma and every sentence for a reason. The good reader, the smart reader, is trying to work out why that is at the beginning of the book or at page ten or at page thirty, and they are trying to get ahead of the writer working out what the writer is doing. And frankly this is exactly what I do. In the first five pages of both East West Street and The Ratline you will find clues about what comes later. You won’t know as you’re reading it, but as you work your way through the book you begin to see why it is there. Why would I make a reference to Wächter’s love for swimming in the beginning of The Ratline? Because later on it becomes absolutely crucial. That, I learnt from Le Carré. He was a great teacher.

Of course, he was fascinated by the moral responsibility of human beings. He was concerned with spies. He was concerned about the spy who comes to a crossroads and has to take a decision: to do the right thing or the wrong thing. I’m interested in that with lawyers. Lawyers who come to a crossroads and are told to do something, and then they ask themselves the question: “Ha, should I do it?”. But there’s an absolute parallelism in the sense that I have learnt from Le Carré about the dilemma of the decent protagonist facing a crossroads. And every human being understands this, because every human being faces these situations to different degrees. It’s essential to the human condition. You can do the right thing, or you can do the wrong thing.

Le Carré appears in The Ratline. Can you tell me about his role in the book?

He does appear in The Ratline because, at a certain point, in dealing with the diaries of Otto Wächter, I discovered that Wächter had fallen into a Cold War espionage story.

Italy in 1949 was a place which was at the forefront of the Cold War. The Americans were very worried that Italy was going to turn communist. And I discovered material that shocked me. The Americans had recruited Italian fascists, Nazis, mass murderers and senior Vatican officials as agents, as spies in the struggle against communism. I was amazed when I came across this material. I didn’t know anything about the Cold War, but I had a neighbor who did. So I called him up and I said: “I’ve got a problem and I really need help. Italy, the Cold War, Austria, recruiting really nasty people”. He said: “Yeah, send me a few documents, bring some cakes, I’ll make tea and let’s talk about it”. I went and the first thing he said to me, which surprised me completely, was: “I was there, I was involved, I was recruiting Nazis”. And he said: “It was morally very complex, because I had been taught that the enemies were the Nazis, they were the worst of the worst, and now they were our friends against the communists”.

And I’ve come to understand that much of Le Carré’s focus on the moral dilemmas and the duplicities of the intelligence services comes from this formative period, when he was nineteen years old in the British Army.

In your last two books you come across unknown manuscripts, lost archives and old libraries. At times, it reminded me of Borges. There is no doubt that research plays a huge role in your novels. To what extent has the fact of being a prominent scholar underpinned the type of books you write? When one gets to the end of your books, one realizes about the amazing amount of research you’ve done.

I wonder if it comes from being a scholar or from being a courtroom litigator. Because the thing is that when you stand up in front of fifteen judges of the International Court of Justice, you know that every word you say has to be accurate. You have to be able to support every word you tell the judges. And I think in these incredible stories, I’m effectively treating the readers as though they are the judges. There are absolute parallels. First, as I said earlier, don’t impose your emotions or your conclusions on the reader. The golden rule for me as a litigator in court is that you never tell a judge what conclusion they should reach. You lay out the material and you hope to encourage the judge through your advocacy to reach the conclusion that you want them to reach. But the moment you say to them: “And this is what you should do”, it’s over, because they don’t want to be told by you what to do. They want to work it out for themselves. They don’t want you, the advocate, to impose a solution upon them. They are the judges, they come up with the solution!

And it’s the same, I think, for the reader. And that strategy, and that act of advocacy —because these books, the writing, are an act of advocacy— is premised on the judge, the reader, having absolute confidence in what they are reading. The moment they have a doubt about the accuracy, the balance, the fairness, the reasonableness of the position you’re taking, you risk losing them. I think that’s the point of connection: the endnotes are there to reinforce in the reader exactly what you’ve articulated. That gives it an authority and an authenticity, and I think it makes it more powerful. But the books are acts of advocacy. I mean, The Ratline, in a sense, is a judgement against Otto Wächter. The judgement that he never got in a court of law.

Another writer who is well-known not only for his unparalleled literary skills, but also for his meticulous research, is precisely your friend Javier Cercas, who also features in The Ratline. Can you tell me about how you two met?

I’ll tell you exactly how we met. It’s very embarrassing. It’s very humiliating for me. After East West Street came out in French I was invited to a conference in Lyon, at the Villa Gillet, which is a very well-known literary festival. I’m a barrister, everything is last minute. You go to court, you prepare at the last minute. And I’m on the train to Lyon from Paris and I realize suddenly than I’m on a panel with some Spanish writer about whom I’ve never heard of [laughs]. It’s so embarrassing. I had never heard of this guy, Javier Cercas, can you believe it?

So I arrive, we’re on the panel, and he starts talking first. He has read East West Street and starts talking about it. And I think: “Oh, my God, this guy is really smart and interesting. He’s read the book with an incredible eye”. Of course, I had never read anything by Javier Cercas, so the panel was a bit, shall we say, complex. But anyway, afterwards we went out for dinner and I loved him. I just thought he was warm, and smart, and funny, and we had a great evening late into the night. And then, when I went back to London the next day, I bought every Javier Cercas book I could find. All of them. I started with Soldiers of Salamis, and then I read every single book that was published in English or French. And I just loved them. He is now one of my very favourite writers. There is nuance in every sentence.

And I think the reason that I loved them is that it resonated with me because I could understand the style of writing, the subject that he was writing about, and I loved the complexity of him taking a true story and then fictionalizing a tiny part of it. As a reader you didn’t know what was fact and what was fiction.

He also played an important role in The Ratline.

Yes, he did. So we became good friends, and then one day I told him about the Wächter book I was writing. And I must have said to him: “I have a problem, because I wanted to see the room in which Wächter died in Rome, in the Santo Spirito Hospital, but I couldn’t get access”. One day Javier rings me up and he says: “Oh, I’m going to Rome. The Pope has invited me to give a lecture on literature and faith”.

Which is funny, because he’s not much of a believer.

He’s not a believer at all.

I know.

But his mother is [laughs]. So anyway, I told him: “If you meet anyone, could you ask them if they could get me into the Santo Spirito?” Then comes June 2019. I’m walking across the mountains with my nineteen-year-old daughter and we have no internet, no phone, nothing, for eighteen hours, while we cross the mountains, at 3,000 metres. We arrive on the other side and on my phone there are many messages from Javier. Eventually I listen to the messages and he says: “I’m in Rome. I gave my lecture. I met someone who’d like to meet you; you have to come tomorrow morning to Rome. I will be there and I will go with you”.

So I went straight from Bolzano to Rome, and we went to the Santo Spirito. But before we went to the Santo Spirito, the bishop said: “Would you like to see the Sistine Chapel, just the two of you?” And so we went. I described it in the book.

But you don’t mention his name in the book, right?

I don’t mention his name. But we go there at 07h30 in the morning and it’s just the two of us in the Sistine Chapel. And I’m sitting there and Javier said he wanted to come to Santo Spirito with me, so I asked him why did he care so much about Wächter, and he said: “Because it is more important to understand the butcher than the victim”.

Which is the opening line of the book.

Yes, and the last section of the book is also him. So he bookends the book. I’m hugely grateful to him.

Cercas is also well-known for his non-fiction novels. Same as you. Although you have very different styles, you both seem to be masters of the genre. And although I think you already answered this question, I’d like to ask it nonetheless: is reality more compelling than fiction?

It can be. Fact is stranger than fiction. One of the famous English historians who reviewed East West Street said in his review: “If this was a novel, fiction, people wouldn’t believe it was possible”. That, I think, indicates that sometimes fact can be stranger than fiction. But I think the two live off of each other. I’m a very big reader and I read a lot of fiction, and what I love about fiction is that it opens up the imagination. Sometimes in ways that non-fiction can’t. So I think you have to read fiction. It’s really really important.

And coming back to reality: let’s talk about the environment and global warming. More specifically, your efforts to introduce the crime of ecocide in the list of international crimes. Is global warming the worst drama of our lifetime?

I mean, there are continuing dramas: war, coronavirus… But I think what’s coming with global warming will dwarf the other challenges that we face. That is why, inspired by Lauterpacht and Lemkin, when I was asked to contribute to the efforts to address this challenge through the law, with the invention of ecocide as a legal concept, I said: “Yes, I want to do this”. But that was an homage to my children, and also to Lauterpacht and Lemkin, to what they managed to do in 1945. They are role models for our social responsibilities as lawyers. Not just to do our professional duty, not just to earn lots of money, but to actually try to improve the world.

We’ve discussed some of the problems of the International Criminal Court. Will it change anything to introduce the crime of ecocide? And even if you manage, won’t it be too late?

No, it won’t. My activities are all about consciousness and hope. I don’t think introducing the crime of ecocide will suddenly change everything, but it will contribute to a change of consciousness, just as the introduction of the concept of crimes against humanity and genocide made us think differently about the powers of the State over the individual and the group. And I think the power of the law is not through the courts and the statute books, but the power of the law is to affect change in human consciousness and open up our imaginations and create a sense of hope. That’s what law can do.

You clearly have two passions: international law and literature.

And my wife.

And your wife. Ok, three passions. But let’s focus only on the other two. If you had to abandon one of two, which one would it be?

Law. But, here’s the problem —because I sort of would like to abandon law, but I can’t—, my friend Hisham Matar says I must never give up the law, because he says the law nourishes me, and if I give up the law, everything else will stop.